The Fokker Spin in Saint Petersburg, 1912

In 1912, Anthony Fokker entered his Spin in an international flying competition in St. Petersburg. Fokker's autobiography The Flying Dutchman from 1931 was for a long time our main source on this event, but additional information has become available from Russia.

During the competition, photos were taken of Fokker and his Spin.

In the first photo (above) we see the Spin with which Fokker participated in the competition.

The second photo (below) offers more. It turns out this Spin had four main wheels and two tail wheels.

The multitude of wheels must have had to do with a difficult part of the race: taking off and landing on a ploughed field.

It can also be seen that a tube is mounted on the starboard side, connecting the rear seat to the front one.

The third photo (below) shows this tube better, which now appears to be in a slightly different position. It must have been an intercom that could be adjusted or moved, towards the mouth or ear. If the Spin's engine had been started and the flight shields had been pulled over the ears, it would have been impossible to hear each other, so such a speaking and listening tube was very useful. Many variations of the Spin have been built, but this example, with six wheels and an intercom, is something we haven't seen before and requires further explanation.

During the competition, Fokker fell in love with a Russian aviator, Lyuba Golancikova, whom we see in the second and third photos. She received flying lessons in the Spin in St. Petersburg, as follows (Fokker writes):

My method was somewhat crude, but effective. She sat in the forward pilot's seat, with the levers within reach…

To make her understand what to do, I grabbed her by the back of her coat, pushed her forward, pulled her back, yanked on her and screamed…”

But why did Fokker actually have to do that now that we know he could use such a handy mouthpiece?

There was no language barrier because she spoke German and French. Or was that intercom not there to begin with and installed at Lyuba's instigation after the harsh lessons?

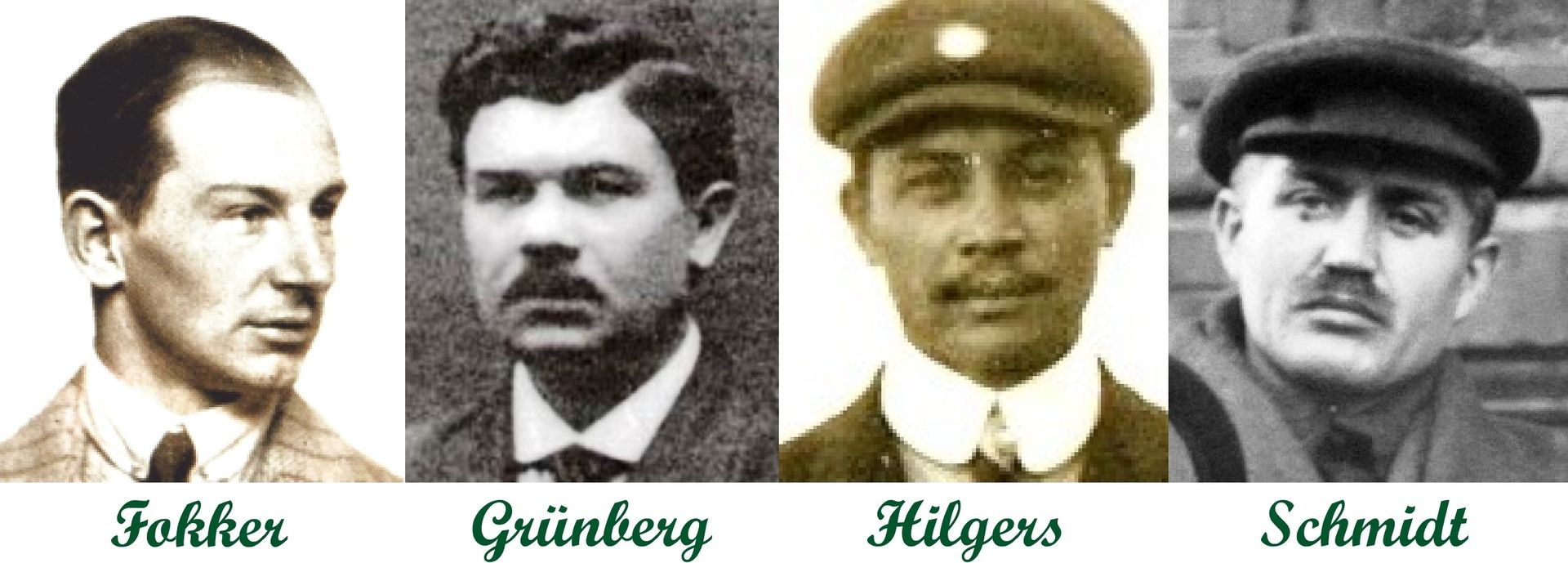

We don't know, but if that's how it happened, the task would probably have been assigned to Hans Schmidt, Fokker's personal mechanic.

We see him in the second photo, but his name is not mentioned anywhere in

The Flying Dutchman.

During the competition, the Spin was flown alternately by Anthony Fokker and Jan Hilgers.

In the fourth photo (above), Jan Hilgers is in the front. He had been sent ahead earlier that year with Hans Schmidt to scout the area and demonstrate the Spin in Helsinfors (now Helsinki), Riga, and Reval (now Tallinn), cities that were then within the borders of the Russian Empire.

Hilgers also doesn't appear anywhere The Flying DutchmanOne person who does appear briefly in this book is Arthur Grünberg, whom Fokker had taken to St. Petersburg as an interpreter and spokesman. Grünberg was originally from Tallinn, worked in Germany, and spoke Estonian, Russian, and German.

Fokker sneers:

“…Grünberg, who had vague Slavic plans to buy a plane from me and act as my agent in Russia…”

What The Flying Dutchman What we don't know is that Arthur Grünberg was the first Estonian to hold a pilot's license, and that he obtained this document before Fokker. Nor is it that, before joining Fokker, Grünberg was employed by Albatros, an aircraft factory that, like Fokker Aeroplanbau, was located in Johannisthal. In that capacity, Grünberg had delivered the first German military aircraft (an Albatros biplane) to the Russians. On that occasion, he had met several key figures from St. Petersburg aviation circles. Grünberg clearly knew what he was talking about, and his "Slavic plans" were certainly less vague than Fokker would have us believe.

Who won the match? The Flying Dutchman reports that Abramovich came first, Sikorsky second, Fokker third.

Strange, because third place would have been awarded with 10,000 rubles and yet Fokker went home empty-handed.

How is that possible? The answer can be found in The Winged S, the autobiography of Igor Sikorsky: only Russian-made aircraft could win prizes.

With a foreign aircraft it was possible to secure an order, but not a cash prize.

Sikorsky received 25,000 rubles for his S-6B being the best Russian aircraft.

Abramovich scored better, but piloted a German-built Wright. Therefore, no prize.

Fokker and Hilgers piloted a German Spin. So, no prize either.

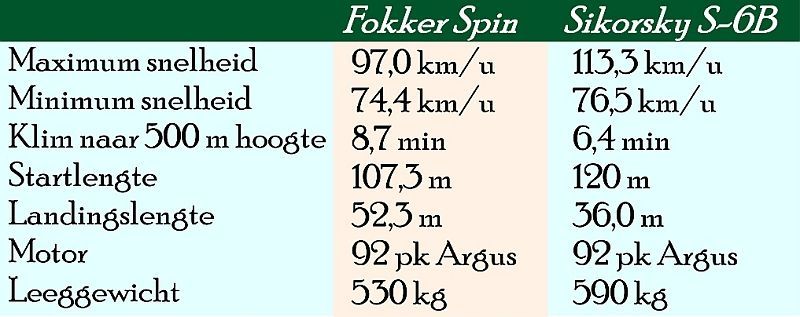

We know that the Spin was almost as good as Sikorsky's S-6B because their performance was compared in the Russian press.

It was noted that the Spin and the S-6B offered similar capabilities as military reconnaissance aircraft, but that the Fokker could land more easily on poor terrain and was better suited as a potential firing platform.

The one who ultimately came out on top was Fokker's then arch-rival Abramovich, who got a foot in the door and managed to sell six Wrights to the Russian air force.

Fokker doesn't mention his name, undoubtedly to cover up his umpteenth defeat against Abramovich: “And the end result was that someone else walked away with the prize, an order for six aircraft.”

Although the Spin attracted a lot of attention (and was nicknamed pa-oek, Russian for spider), Fokker failed to gain a commercial foothold in Russia.

A huge setback, as he was short of cash in those days. That would change completely in the 1920s, when he became a multimillionaire and countless Fokkers were flying around the Soviet Union.

Sources:

- The Flying Dutchman, A.H.G. Fokker & B. Gould, pp. 104-111 (1931)

- The Winged S, II Sikorsky, p. 49 (1956)

- See more 1938 г., V.B. Shavrov, pp. 145-146 (1978)

- Die deutsche Flugzeuge in Russian and Soviet Services 1914-1951, Band 1, A. Alexandrov & G. Petrov, pp. 9-10 (1997)

- The pioneering years of Dutch aviation, KJ Sijsling, pp. 93-98 (2014)

- Anthony Fokker - A Bygone Life, M. Dierikx, pp. 62-88 (2015)

© René Demets

With thanks to Gennady Petrov and Viktor Koelikov (who provided the photos), Mart Enneveer, Marc Dierikx and Michael Schmidt.