The Eagle of Lille

Author: Annabel Junge

(Published in "The Emperor's Aces of Air", Aspekt Publishers 2020)

Introduction

Max Immelmann was one of the most famous German aces. He lived only 26 years, yet he managed to make a remarkable contribution to that short life. As a pilot in the First World War, he achieved seventeen victories, earning him several high honors. Among them was the Pour le Mérite, nicknamed der Blaue Max (the Blue Max)—a reference to Max Immelmann.

The German press called him the Eagle of Lille. Even his enemies had great respect for him and considered it an honor to be shot by him.

Together with the other famous German ace Oswald Boelcke, he flew Germany's first fighter plane, the Fokker Eindecker IV.

During his lifetime, Max Immelmann achieved heroic status, and even today, his name lives on. The Immelmann maneuver, for example, remains a hallmark of aviation, and since 1993, the Tactical Air Squadron 51—formerly known as Enlightenment Squadron 51—has borne the name "Immelmann Squadron" in commemoration of this renowned pilot.

The early years

Max Immelmann was born on September 21, 1890, in Dresden, Saxony. His father, Franz Immelmann, owned a cardboard factory. He suffered from tuberculosis and died when Max was seven.

His mother, Gertrude Grimmer, was the daughter of the Royal Saxon Auditor General. Gertrude was not in good physical condition, and neither were her three children. His younger brother and sister teetered on the brink of death in their early years. Since doctors could not adequately help her children recover, Gertrude turned to alternative medicine. After trying some methods on herself, she then applied them to her children, and with success. All three grew up to be strong children.

Because of these experiences, Gertrude remained open to modern methods and new developments. As a result of this changing attitude, she put her children on a vegetarian diet and forbade them from drinking alcohol and smoking. Max would also remain a non-smoker, teetotaler, and vegetarian for the rest of his life, although he did eat meat while in the field during the war.

From a young age, Max had a keen interest in technology. It was, after all, the century in which technical ingenuity and machinery were booming. He took everything apart to see how it worked. This applied to his toys, but later also to his bicycle, motorcycle, car, and even his airplane. However, he also knew how to put everything back together correctly after his research.

Max was also a very athletic boy. He was a good gymnast, figure cyclist, and floor acrobat.

In 1905, he enrolled in the Cadet Corps in Dresden. In 1911, he joined Eisenbahnregiment (Railway Regiment) No. 2 as a Fähnrich. When his military service ended, Max left the army in March 1912 and went to study mechanical engineering in Dresden.

Wartime career

In the early 20'sste century, aviation was in its early 20sste century was still in its infancy, yet Europe was already captivated by the Wright brothers and Louis Blériot.

With gliders and the first primitive powered aircraft, the possibilities of flight were just beginning to be discovered. People capable of moving through the air caused great astonishment. To familiarize the public with this remarkable development for its time, international air shows were held regularly. The ability to fly had fascinated humanity for centuries, but since 1903, thanks to the Wright Brothers, flight was no longer a dream but a reality. From that moment on, the skies could be conquered! The importance of this development for humanity was first demonstrated during the First World War.

When war broke out, many pilots hoped to contribute to the fight. But nothing could be further from the truth. Military commanders were unconvinced of the usefulness of aircraft. They considered them too fragile and too dependent on the wind. The aircraft were also vulnerable for another reason: neither the pilots nor the aircraft were armed or armored.

But on the ground, the battle was difficult. The soldiers could see no further than the nearest hill. Aviators, however, could soar above the hills and become the eyes of the artillery. After much deliberation, the military commanders relented, and aircraft were deployed for reconnaissance. The results were so positive that it was soon decided to also have the scouts take photographs of enemy positions. Unlike other countries, the German military leadership initially relied heavily on airships. However, these slow and cumbersome contraptions had their limitations and were therefore not very useful. Meanwhile, aircraft were undergoing rapid development, and an effective air force was born. Germany realized that military progress was necessary if it wanted to compete. Crown Prince Heinrich of Prussia supported the German government's call to raise funds for the improvement of German aviation, and thus began a new milestone in aviation history that would prove to be of great significance in the progression of the First World War. And Max Immelmann would play a significant role in this.

When war broke out, Max Immelmann was called up for active duty as a reserve officer. His first posting was Eisenbahnregiment Nr. 1, but the young conscript found it rather boring. The army leadership decided to transfer him to the Die Fliegertruppe des deutschen Kaiserreiches (later known as the Luftstreitkräfte), the air force of the German Empire, which had been established in 1910. A golden age began there for Immelmann. In November 1914, he was sent to Berlin for pilot training at Johannisthal airfield. This airfield had been constructed in 1909. It opened just weeks after the world's first airfield was established in Rheims, France, and it became an active hub for aviation. Several flight schools opened there, and military pilots were also trained in Johannisthal.

From February to April 1915, Immelmann served as a pilot with Feldflieger Abteilung (FFA) 10. During this time, he took the Flight Equipment Pilot Exams 1 and 1, and on March 26th, also the third exam. He passed all his exams, and from May 1915 onward, the Döberitz military training area near Berlin became Immelmann's permanent base. He now served with the recently formed FFA 62. After completing his basic training, Immelmann was stationed in northern France as an aerial reconnaissance aircraft and was given the use of an LVG B1 (Luft Verkehrs Gesellschaft). One of the two-seater aircraft with which his unit was equipped, alongside the Gothas and Albatrosses. The LVG B1 was ahead of its time. The aircraft was less cumbersome and therefore faster and more powerful than the aircraft used until then. It could also reach higher altitudes, unlike the aircraft of its predecessors. Immelmann was also assigned a scout, Leutnant Erhardt von Teubern. The two men had known each other from the Cadet Corps.

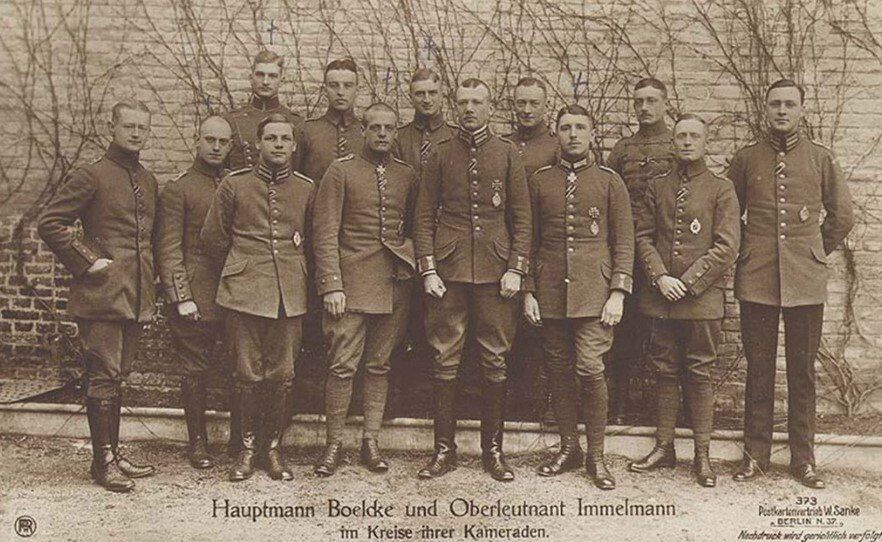

In early April 1915, they were transferred to La Brayelle air base near Douai, northern France, which was then in German hands. They served there under Hauptmann Kastner. Max Immelmann was an odd figure to his comrades, as he steered clear of parties and drinking binges. His best friend was his dog, a gray Mastiff named Tyras, who always slept on his master's bed, and his mother was the only person to whom he wrote extensively about his experiences in his many letters. These same letters revealed his early affinity with a fellow pilot in FFA 62: the 24-year-old Lieutenant Oswald Boelcke, eight months younger than him. This pilot was already a veteran with over fifty missions to his credit and had also received the Iron Cross 2nd Class. "We're a good match," Immelmann wrote in one of his letters. "Neither of us smokes, and we hardly drink alcohol… he [Boelcke, ed.] has been flying since the beginning of the war and was at the front for a long time." Because of these descriptions, it was always assumed that Immelmann and Boelcke were good friends, but letters from Boelcke, recovered after the fall of the Wall, revealed that there had been no close friendship. The two pilots did, however, often fly together. In fact, Oswald Boelcke and Max Immelmann were the precursors of what later became common in military aviation: the leader and his wingman (i.e., his supporter in dangerous situations).

Besides the Germans, pilots from the British Royal Flying Corps and the French Aéronautique Militaire were also active in northern French airspace. The differences in flying styles between countries soon became apparent. The British remained conservative regarding aerial warfare. Their method of selecting pilots was based on background. Someone from upper-class backgrounds was allowed to undergo a few weeks of flight training. If they passed, which was by no means always the case, the newly qualified pilot was sent to the front. The French, on the other hand, considered mechanical knowledge and driving skills important prerequisites for their pilots. Their motto was: whoever could drive, could fly. For the Germans, previous combat experience was decisive, but even more so, the character of the aspiring military pilot. Such a man had to be made of steel, bold, and brave. The German pilots certainly did not lack courage. They soon became known for the superior strength with which they carried out attacks. Immelmann so aptly described this approach in one of his letters: "...so we usually climb to 2,800 to 3,000 meters. We carry out air surveillance duties at altitudes of 3,500 to 3,700 meters and higher. You go so high because you have a better chance of seeing enemy aircraft and being able to attack them from above. Because it's easier and more convenient to shoot down than up."

Nevertheless, Immelmann learned firsthand that courage alone could not win the battle. During a reconnaissance flight over the French lines near Arres on June 3, 1915, after encounters with enemy aircraft in the airspace earlier that day, Immelmann and von Teubern were intercepted by a Farman biplane equipped with a machine gun. It was an unfair fight, because as a scout, Immelmann, unlike his pursuer, did not have a weapon. Although Immelmann tried to stay in the air as long as possible so that von Teubern could take the necessary photographs, they could not escape the Frenchman's barrage. Despite the pilot's skillful flying, Immelmann was forced to abandon the fight. Nevertheless, he managed to land safely behind German lines. After landing, they examined their aircraft. Six bullets had barely damaged the plane, but the metal cowling covering the engine was riddled. Another bullet had struck the spar, the structure to which the engine was attached. Had it broken, the entire aircraft would have collapsed in mid-air. For saving his aircraft, the young pilot was awarded the Iron Cross 2.the Class.

The tide must be turned

Max Immelmann had also learned a valuable lesson: there's no justice in the airspace when one pilot has bullets and the other can't do anything. This had to change, and preferably as soon as possible! In July 1915, the FFA 62 received its first armed two-seater, an LVG C1 with a Parabellum MG14 for reconnaissance. The C-planes were primarily designed for reconnaissance and escort duties. As a more experienced pilot, Boelcke was naturally assigned the new plane, and Immelmann received Boelcke's "old" plane. But Immelmann came up with a brilliant solution for himself and his scout. They mounted a captured French machine gun on their LVG. "My plane may be an improvisation, but at least my observer can rattle the gun, and that makes a lasting impression on the French," he wrote. "Things are going to change from now on," he stated resolutely. With a sense of satisfaction, the men took to the skies again. But as fantastic as the solution had seemed on the ground, its effect in the air was less impressive. When firing, the hail of bullets often hit the propeller, and on numerous occasions, a bullet even destroyed a propeller blade. Engineers had to go back to the drawing board to devise new solutions that could guarantee the safety of the pilots, and surprisingly, the enemy played a significant role in that development.

The first real fighter plane - Fokker Eindecker

Immelmann as a fighter pilot

Earlier that year, on April 18th, a dogfight took place between the French and the Germans. French pilot Roland Garros had already shot down three German aircraft when he himself was hit by a German pilot. Garros ended up behind enemy lines with his plane, where he was awaited by German soldiers for interrogation. Meanwhile, his plane was subjected to a critical examination, and an interesting discovery was made. Garros had cleverly solved the problem of propellers firing during fire by attaching steel wedges to the blades, which deflected the bullets. Dutch aircraft manufacturer Antony Fokker, employed by the Germans, was tasked with further developing this invention. Fokker had previously offered his services to the British, but they had rejected him. The Germans were willing to utilize the Dutchman's expertise, and that proved to be a wise decision. Fokker came up with an ingenious invention: a synchronization mechanism, or interruption mechanism. This mechanism fired the bullets precisely between the propeller blades.

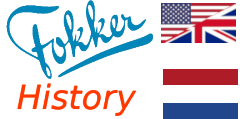

Fokker had been busy for some time with a new design to improve his Eindecker aircraft. The first Eindecker dated from 1913, an aircraft that no longer had room for a reconnaissance pilot. There was only room for the pilot. The latest Eindecker, the fourth in the series, was not a spectacular design. Its speed was only 140 km/h (87 mph), and the aircraft could only stay airborne for an hour and a half at most. Its strength, however, lay in its powerful engine, which allowed the aircraft to be equipped with up to three machine guns, significantly increasing its firepower. Fokker now used this Eindecker IV to implement the synchronization mechanism. Fokker had mounted the machine gun, the MG 8 'Spandau', on the engine cowling and synchronized it so that the gun fired between the propeller blades. In tests, the mechanism worked perfectly, Fokker claimed, although he damaged his own propeller during a demonstration in Essen when the mechanism failed. But on May 23rd, at the FFA 62 air base in Berlin, he demonstrated that the interrupter mechanism was now functioning properly. However, that test wasn't convincing enough for the German commanders. They really wanted to see the mechanism in action and suggested to Fokker that he might shoot down a Frenchman to prove the excellent effectiveness of his invention. Fokker wasn't exactly thrilled about donning a German uniform and going to the front, but he had no choice. He flew his Eindecker several times to demonstrate how well the mechanism worked, without actually shooting down a French aircraft, as that was a bit too much for Fokker. After all, he was Dutch, not German. He believed the Germans were man enough to handle things themselves. A view that didn't meet the German military leadership's understanding. In their view, Fokker's gunnery exercises didn't meet their requirements. To reach an agreement, an experienced military pilot still had to properly test the aircraft. That honor fell to Lieutenant Kurt Wintgers. When he forced an Allied aircraft to land, the commanders were finally convinced. A decision with far-reaching consequences. The effect of the new interrupt mechanism was enormous. Less than two weeks later, six Fokker Eindeckers, now equipped with two or three machine guns, were wreaking havoc in enemy airspace. Thanks to this invention, German aviators had become true masters of the skies. By the end of July 1915, fifteen Fokker Eindeckers were operational with various units. The war, and air warfare in particular, had suddenly taken a completely different turn.

To teach the pilots to fly the Eindecker, the men were sent to Fokker's flight school in Schwerin. Immelmann, newly promoted to lieutenant, was reluctant to go to Schwerin. Fokker accommodated the young pilot by stationing an unarmed training aircraft in northern France. Immelmann was immediately enthusiastic about the new aircraft, which was both light and fast. Immelmann's response: "You want to know the difference between an LVG biplane and a Fokker monoplane? The LVG primarily has a stationary engine, while the Fokker has a rotary engine. That is, in the LVG engine, the cylinders are arranged side by side (or one behind the other), while the Fokker's are arranged in a star configuration, and the entire engine rotates. All in all, the LVG weighs approximately twenty-two hundredweight (Zentner = old size, approximately 50 kg), while the Fokker weighs only about six hundred hundredweight."

This was the plane he longed to fly. "A machine truly designed for combating enemy fighters, not for reconnaissance," he declared after his first flight. Moreover, the older Fokker types often suffered from engine problems, and with the arrival of this new aircraft, pilots hoped such problems would become a thing of the past. But Immelmann had to wait until his turn to fly the newest type. As usual, Oswald Boelcke was allowed to fly the first Eindecker IV, and his previous plane was again assigned to Immelmann. The young pilot, however, had no qualms about the decision. It was a minor promotion, after all, and it was only natural that Boelcke, as a more experienced pilot, would be given preference over him. Yet, fate would turn on Immelmann sooner than he had anticipated.

On August 1, 1915, a bombing raid took place over Douai. German pilots, including Boelcke, rushed to take off with their planes to engage the British B.E.2 light bombers. Immelmann wanted to go too, but his scout considered a flight hopeless. Immelmann watched the spectacle high above them with dismay. At least ten enemy aircraft flew through the airspace. Immelmann thought no longer and retrieved a second Fokker Eindecker IV from the hangar and took off. He saw Boelcke flying directly behind one of the bombers, but its machine gun malfunctioned. Boelcke was forced to abandon the dogfight and dived down. Immelmann decided to fight on, having come within firing range of the enemy. His comrade, meanwhile, was watching the dogfight from the ground with some trepidation. Boelcke was convinced that Immelmann's plane would be shot down. But Immelmann already felt completely at home in the new Fokker. As if he'd never flown anything else, he sliced through the airspace. He attacked a BE2 and, despite his machine gun briefly malfunctioning, wounded the pilot, who was forced to make an emergency landing. Immelmann dove after the plane, as he wrote in one of his many letters to his mother: "Like a hawk, I swooped down on the enemy, firing my MG. For a moment, I believed I was going to fly right into them. I'd fired about 60 rounds when my gun jammed. That was really tricky, because I needed both hands to correct the malfunction—I had to fly completely hands-free, which was new and strange to me, but I managed." Second Lieutenant William Reid fought back bravely. He flew with his left hand while firing a pistol with his right. But he was no match for a hail of 450 rounds, even though "only" forty bullets hit their target. These impacts, however, occurred at a speed of 130 km/h. Reid suffered a quadruple fracture to his left arm, and his plane's engine stopped, forcing an emergency landing. Max Immelmann landed nearby just behind him. He disembarked and walked over to Reid. The two men shook hands, and while saying, "You are my prisoner," Immelmann pulled the British pilot from the wreckage. He then administered first aid and sent the pilot and his observer to a doctor. This also gave him the opportunity to examine the plane and saw that it was riddled with bullets. For this event, which was also his first officially confirmed victory, Immelmann received the Iron Cross First Class.

With the downing of this first aircraft by Immelmann, the so-called "Fokker Scourge" began. This heralded an era of unchallenged German dominance in French airspace. The new Fokker Eindeckers would inflict heavy losses on both the British troops of the Royal Flying Corps and the French troops of the Aéronautique Militaire in 1916.

The Fokker Plague 1 August 1915 – 18 June 1916

The victories had convinced the German military leadership that the German air force now possessed a weapon capable of dominating the skies. Initially, the Feldflieger-Abteilungen were assigned two Fokkers per sector, intended to protect the two-seaters, as reconnaissance remained the primary task. This ensured that there were Fokkers in every sector, and the two-seaters enjoyed relative peace. The Fokker pilots were expressly forbidden to fly behind enemy lines for fear that the Allies would capture a Fokker aircraft. This prohibition, however, implied that German pilots had to break off the pursuit as soon as the enemy line came into view. Many Allied pilots were thus able to escape their pursuers. But outside enemy lines, the Eindeckers were untouchable from the autumn of 1915 until the summer of 1916. Besides Immelmann and Boelcke, other gifted German pilots also became known for their numerous aerial victories. The first German aces were Oswald Boelcke, Max Immelmann, Kurt Wintgens, Otto Parschau, Walter Höhndorf, Wilhelm Frankl, Rudolf Berthold, Gustav Leffers, Hans-Joachim Buddecke, Ernst Freiherr von Althaus, and Max von Mulzer, a pupil of Immelmann. These victories were also due to the new tactics employed by Immelmann and Boelcke. Instead of individual attacks, they now flew in small squadrons. In the first month alone, these German fighter pilots managed to shoot down 82 enemy aircraft, resulting in 74 kills.

The British had no answer to these powerful new German air weapons. Their morale suffered terribly from the continued German successes. The lack of a synchronization system forced them to devise other methods to defeat the enemy. For the time being, they still relied on their so-called "push-pull" aircraft. (In these types of aircraft, the propeller was mounted behind the engine.) It would take another year before they solved the propeller problem. The British press lamented bitterly about the fate of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) crews, who seemed to be nothing more than "Fokker fodder"—fodder for the Fokkers! This was originally a statement made by British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, who had openly complained that all British aircraft were rubbish compared to the German Fokkers. The British press therefore coined a fitting term for the air dominance now underway: Fokker Scourge.

Yet British engineers weren't sitting idle either. The FE 2b (Farman Experimental 2, a two-seater) took to the skies. This rear-engined aircraft, equipped with two machine guns, was often a rival to the Eindecker. It even earned the nickname "fee" (tip) because of its type designation.

French pilots were also awaiting new aircraft types better equipped for intense aerial combat. Until then, they armed their Nieuport fighters with a machine gun on the upper wings.

The German pilots were becoming true national heroes. People traveled from far and wide to see and meet their idols like Max Immelmann in person. By the end of October, Immelmann had achieved his fifth victory, shooting down a Vickers FB5 "Gun Bus," and his name was mentioned in military communiqués.

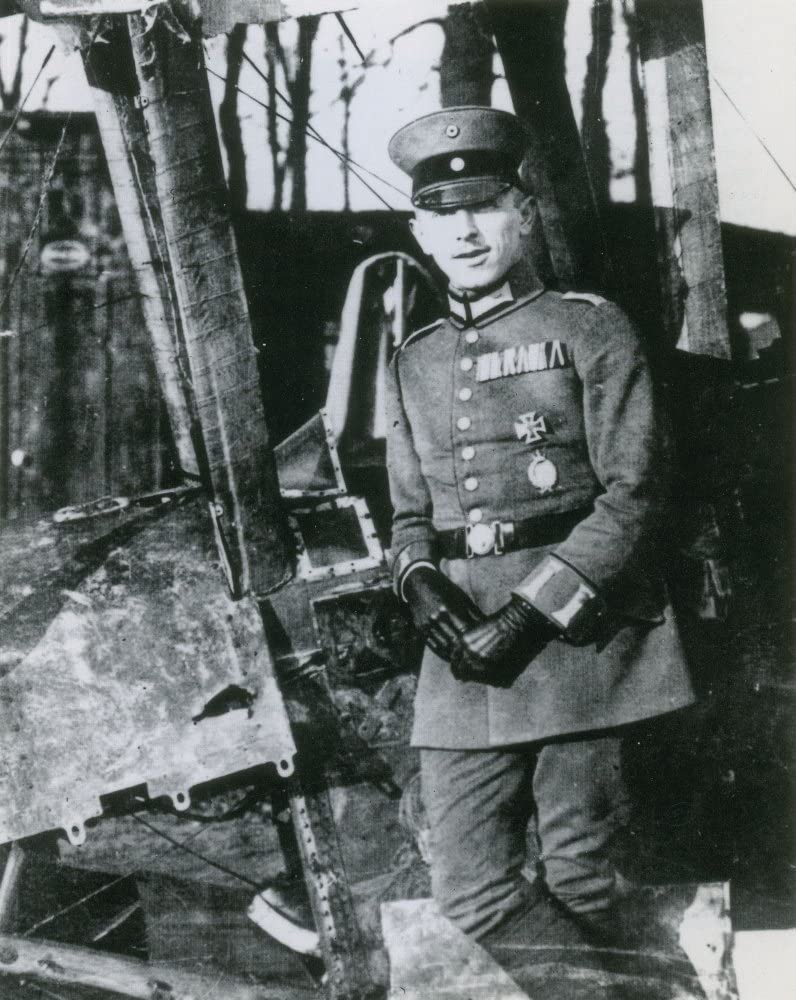

"Now I will no longer object to being written up in the newspapers, because I've seen how everyone at home follows my successes," he wrote in one of his letters. And the newspapers took great interest in Max Immelmann. Anecdotes and legends about the young pilot were often published in the papers. It was also the German press that nicknamed Immelmann, Der Adler von Lille, after his heroic action over Lille a few months later in November. As the only German aviator, Immelmann had been responsible for the air defense of the city of Lille. All this publicity led to even more attention. Immelmann frequently dined with dignitaries or members of royal and imperial families. As gifts, he often received commemorative dishes, silver cups of honor, cutlery, and signed photographs of nobles. From the German Automobile Club, he received a gold tie pin studded with diamonds. Children wrote letters to him, because everyone wanted to know Immelmann or at least have a picture taken with him. The young, ambitious pilot loved posing for the camera. His vanity often led him to fly with his medals pinned on, making him look good in photos when he posed in front of a wreckage shot down by a plane. A fellow pilot once recounted that Immelmann initially wasn't at all pretentious, but as he racked up more victories, the young flying ace became vain, for as his victories grew, so did his decorations. His comrades mockingly called him "Your Majesty." Three more victories followed in September. For his sixth victory, Immelmann was awarded the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern. This made him the second pilot, after Boelcke, and at the time, the only pilots to receive this distinction. The hero worship went so far that his old Fokker, with which Immelmann had shot down five English aircraft, was shipped to Berlin to be put on display at the Zeughaus Museum in March 1916. (In 1940 the aircraft was destroyed by the first RAF bombing raids.)

The important year 1916

On December 15, Immelmann shot down his seventh British aircraft. With the Fokker Eindecker IV, Max Immelmann had become a true fighter pilot. He was greatly feared by his enemies, although Immelmann achieved few confirmed victories from early January to early March 1916. At that time, he actually owed his illustrious status more to his reputation than to his triumphs. This reputation was also known to the British, as became clear during an encounter with a British pilot he had shot down shortly before. It was his eighth victory at that time. Second Lieutenant Herbert Thomas Kemp just managed to land his Vickers, followed by Immelmann, and then they both observed the burning aircraft. Kemp asked the gunner if he was Immelmann. He answered in the affirmative. Kemp then replied that he considered it an honor to have been shot down by such a great ace.

Although Max Immelmann came across as an indifferent gunner, more tenacious than skillful, despite all his successes, he wasn't out for outright destruction. He preferred to capture his opponents alive and enjoy striking up conversations with them. The pilots often knew each other from the pre-war era, when they were regulars at air shows. The young aviator himself claimed he didn't use tricks during his offensive. He had a habit of hovering behind German lines, awaiting British reconnaissance aircraft. Then he'd swoop in behind their tails, preferably with the sun at his back. The first "acquaintance" came with his machine gun, which unleashed a barrage on the enemy aircraft. In most cases, the enemy fell immediately. However, if the pilot did manage to stay airborne, Immelmann resorted to other maneuvers, which the clumsy FE2c, for example, was no match for. The British pilots were repeatedly surprised by him.

Because Max Immelmann had racked up an impressive number of aerial victories in a very short time, he considered himself the first German ace on January 12, 1916. This was the day he achieved his eighth victory. Normally, five victories were sufficient for the title of flying ace, but in Germany, eight victories were required to be recognized as an air ace and be eligible for the prestigious award Pour le Mérite. Later, this requirement was raised to sixteen.

However, when Immelmann returned to Douai, it turned out that Boelcke, stationed in Rethel near Verdun, where he was leading a new Kampfeinzitzerkommando against the French, had also achieved his eighth victory almost simultaneously. According to Immelmann himself, he was genuinely delighted with Boelcke's victory. For their achievement, both pilots were awarded the Order. They were the first pilots and junior officers to receive this distinction. Immelmann was the first to receive the coveted blue-enameled cross from Kaiser Wilhelm II. This occurred on the same day as his eighth victory. Legend has it that this medal was therefore nicknamed "Der blaue Max" (The Blue Max) within the German air force in honor of Immelmann. Incidentally, the name was adopted by the British. Oswald Boelcke received the award shortly afterward. Two days later, Boelcke scored again, and this time Immelmann followed hot on his heels. A veritable "ace race" between the two pilots raged for the next four months. March 1916 proved to be Immelmann's best month, with five victories, and even two in one evening. But Boelcke kept pace with his comrade. Their combined total stood at 13 victories by the end of March. Max Immelmann—after his twelfth victory at the end of March 1916—was the only one to receive the highest bravery award in his Saxon homeland, the Militär-St. Heinrichs-Orden Second Class.

The last dogfight for Max Immelmann

And also the end of the Fokker Plague

In principle, the final phase began at the end of February 1916 with the Battle of Verdun. For the French, the long-awaited new aircraft, superior to the Eindecker, had finally become a reality. With the Nieuport 11 Bebe, they became formidable opponents of the Germans. The British had not been idle either. The Airco DH.2 was also sighted in the skies above the front lines. Like the French Nieuport, this British aircraft was faster and more maneuverable. With the support of British biplanes such as the Vickers FB 5 (nicknamed the Gun Bus) and the FE2b, these aircraft were now capable of becoming powerful opponents for the Fokker Eindecker. Combat tactics also changed. The British deployed special squadrons. Many aircraft in the air simultaneously could eliminate more opponents. And so, the air battle swung back in favor of the Allies.

The German pilots experienced more and more defeats. Max Immelmann's glorious days of victory were also quickly numbered. In the final weeks of April, the young pilot, whose star had already risen considerably, was confronted with a serious setback. Two Airco DH.2 pusher biplanes of the 24th Air Force were in the airspace.ste A squadron of the Royal Flying Corps appeared. Immelmann pursued them, and initially his chances seemed favorable, but the new synchronization mechanism malfunctioned. This time, he was the hunted. The two British pilots worked together brilliantly during the dogfight, hitting Immelmann's aircraft at least eleven times, including the tank and the propeller. Immelmann was only able to save himself by diving. This immensely distressing experience had a deep impact on the once-proud pilot. From then on, according to his comrades, his normally firm gait weakened, and he appeared very nervous.

Another month later, on May 31, Max Immelmann,

Max Ritter von Mulzer and another German pilot attacked a formation of seven British Vickers fighter planes between Bapaume and Cambrai. Immelmann was flying a Fokker E.IV, equipped with two machine guns. But when he fired a long burst, the synchronization mechanism failed again. A stream of bullets clipped the tip of a propeller blade, and the aircraft began to shake violently. The aircraft's Oberursel engine nearly detached from its struts. With difficulty, Immelmann managed to shut down the engine, after which the aircraft went into an uncontrolled dive. Immelmann managed to land his Fokker along the Cambrai-Douai road in an emergency.

A definitive end to the Fokker Plague came on June 18, 1916, when Immelmann's last dogfight broke out. On that particular afternoon, the skies were busy. Immelmann led the four Eindeckers on a reconnaissance flight over Sallaumines in northern France. Simultaneously, eight FE2b aircraft of the 25thste Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps was conducting a reconnaissance mission. They had just flown over the lines near Arras to photograph the German infantry and artillery positions in that area. A confrontation ensued, but the "Fees" were no easy target. The aircraft were equipped with one machine gun firing forward and another mounted upward to fire backward over the upper wing and propeller. The dogfight continued, covering an area of approximately 30 square miles. Late in the afternoon, around five o'clock, Immelmann finally managed to force a plane to land near Arras. Both the British pilot and his observer had been wounded. However, Immelmann's own aircraft had also suffered some damage. The E.IV had taken a serious beating, with its struts and wings sustaining considerable damage. A landing was therefore inevitable. While Immelmann's aircraft was being repaired, the 25ste In the evening, the squadron launched another raid over enemy lines. Immelmann hurried to his old E.III to take off and rejoin his men.

Once airborne, at an altitude of approximately 200 meters, the German pilot immediately found himself caught up in one of the largest aerial battles to date. Over Loos, ten Fokkers were engaged in combat with eleven British intruders, including four "Fees." From the ground, German anti-aircraft batteries could be heard, constantly firing shells. During this chaos, Immelmann managed to chase the FE2b, flown by Lieutenant J.R.B. Savage, behind the German lines, firing a white flare to warn the anti-aircraft guns to cease fire. Meanwhile, his machine guns rattled continuously, and at 9:45 p.m., his 17the Victory was a fact. Just as in the previous victory on this day, the pilot was dead and his observer wounded. It was the second time in his life that Immelmann had shot down two opponents in one day. But the hunt wasn't over yet for him. He still had ammunition, and another FE2b had already caught his attention. But behind him, a "Fee" also appeared. Second Lieutenant George Reynolds McCubbin had come very close to the Fokker. As soon as Immelmann noticed a Fee on his tail, he banked to escape his pursuer. At that crucial moment, a burst rang out from the Lewis machine gun mounted on the front of the "Fee." Scout and gunner Corporal James H. Waller had opened fire just as Immelmann passed in front of them. The Fokker was immediately out of control. Witnesses from the ground saw Immelmann's aircraft suddenly start to shake during a dive. The aircraft seemed to be thrown back and forth through the air, and the forces on it became so great that the tail section of the E.III broke off. The plane had become nothing more than a falling object. The wings were also torn off en route. There was nothing that could save Immelmann (it wouldn't be until 1918 that German crews were issued parachutes). He hurtled downward at full speed, facing his end. With a tremendous crash, the Fokker's fuselage slammed into the ground. Two pieces of the aircraft were found a few hundred meters away.

German soldiers of the 6the The first soldiers on the scene were shocked by the sight of the mangled aircraft. Only the Oberursel engine remained completely intact. The pilot's body had been crushed, making identification considerably more difficult. Opening the jacket revealed the blue Pour le Mérite and a handkerchief embroidered with the initials MI. This proved convincingly to the bystanders that these were the remains of Max Immelmann. The pilot was taken to Douai hospital.

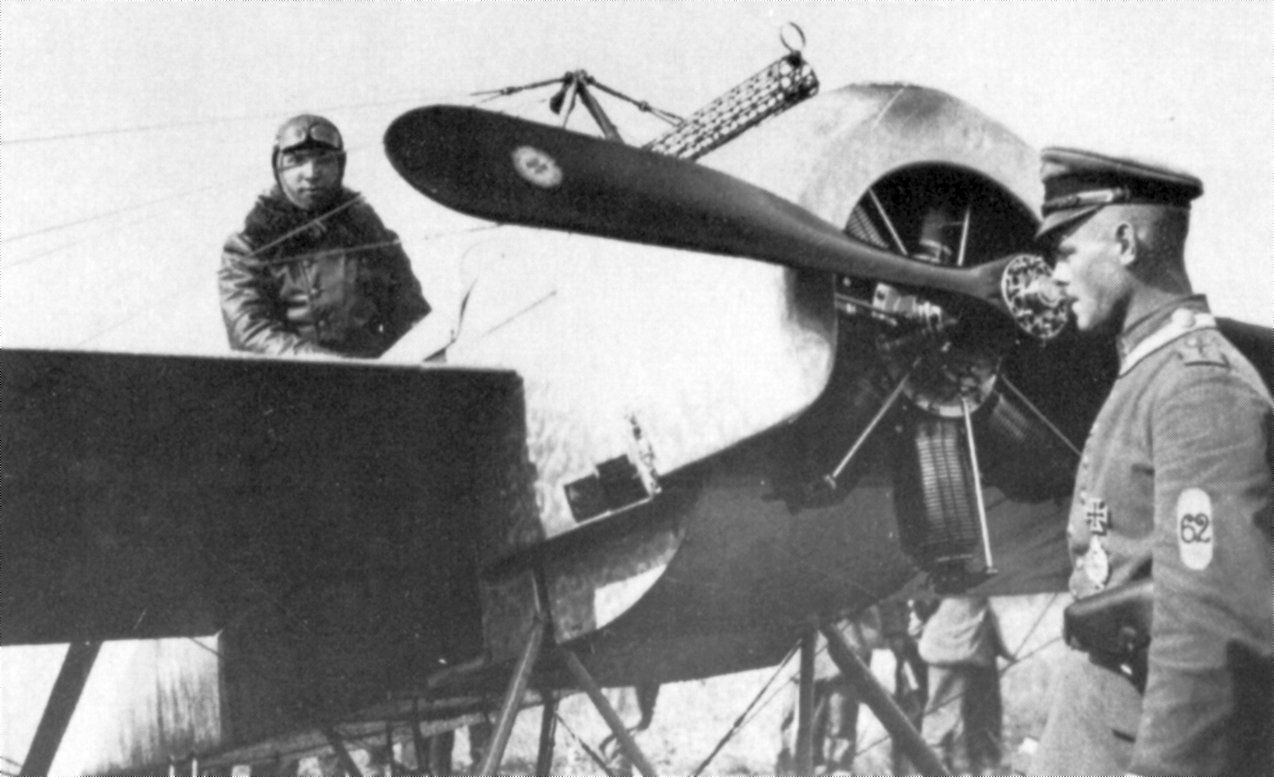

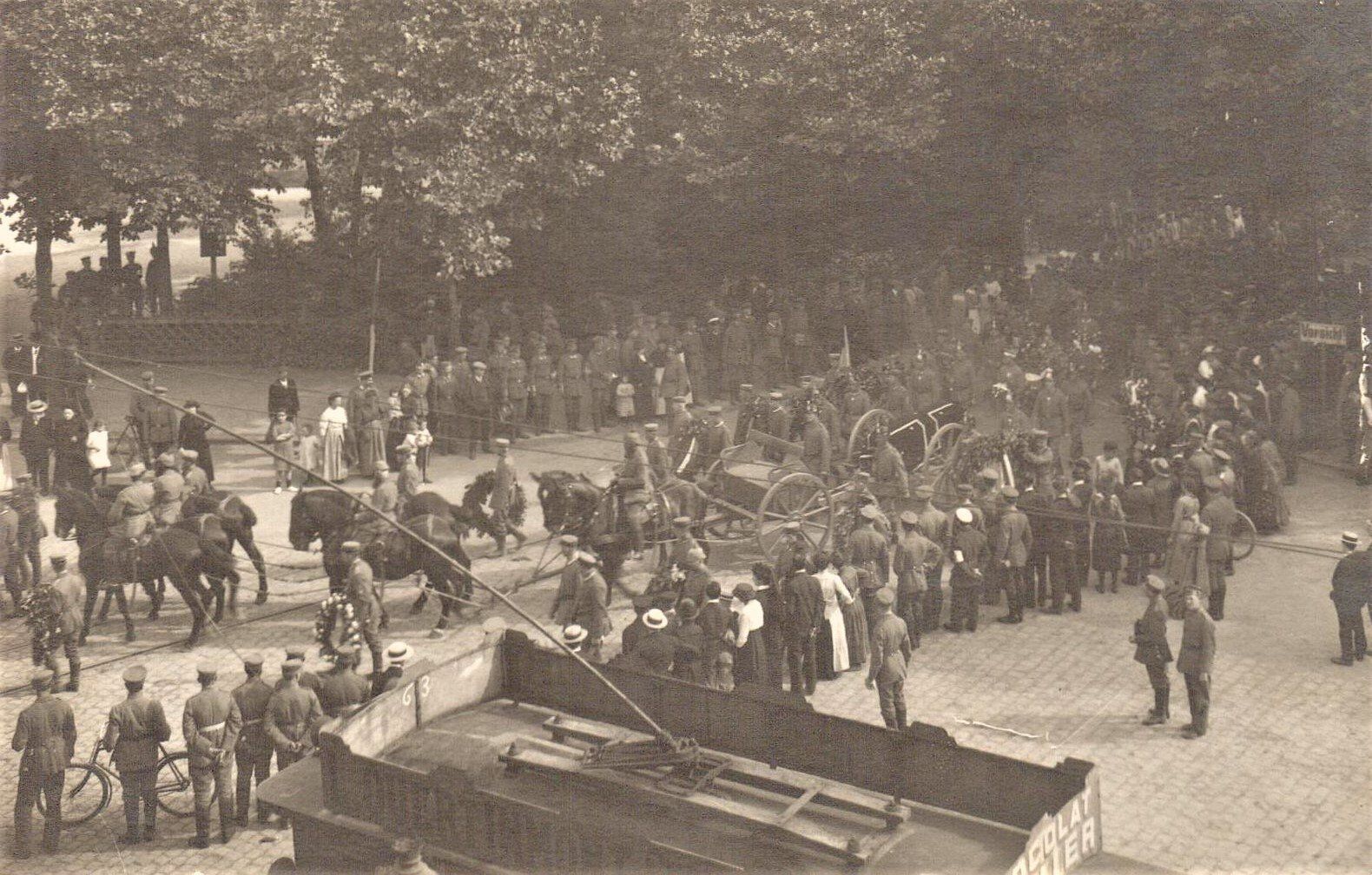

A grand tribute took place on June 22. The 6the The army and the troops at the front said goodbye to their beloved pilot, who would soon return home to be laid to rest in his birthplace, Dresden. In the hospital garden, surrounded by laurel and cypress trees, stood the catafalque with the coffin, laden with wreaths and roses. The whole was flanked by four pillars, each with an iron candelabra, from which glowing flames rose heavenward. The guard of honor was formed by the men who had previously maintained his Fokker, and before them stood a vast crowd of field-gray soldiers. Among those present were Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, who commanded the army unit to which Immelmann belonged; Prince Ernst Heinrich, son of the King of Saxony; all the generals of the 6th Army; and representatives of all the aviation units of the Western Front. The air force staff officer honored Max Immelmann on behalf of the air corps as a man and a soldier.

As soon as the British discovered who had been in that Fokker, the propaganda campaign erupted. Pilot McCubbin and scout Waller were awarded the Distinguished Service Order and the Distinguished Service Medal. Waller was also awarded the sergeant's stripes. Morale among the British pilots immediately improved significantly. Nevertheless, the British also showed their respect to the fallen ace. Over a German airfield, they dropped a wreath in memory of Immelmann with the message "for our brave, chivalrous enemy."

However, for both the German armed forces and the German people, the devastation at the death of their beloved hero was immense. Max Immelmann's death was almost impossible for anyone to grasp; after all, he had always been invincible. All sorts of rumors about the cause quickly arose. An investigation was necessary to uncover the truth. Ultimately, three investigations were conducted: an official military investigation, a private investigation by Anthony Fokker, and a private investigation by Frantz Immelmann, Max's brother and biographer. But a clear conclusion remained elusive. According to the military experts, the Fokker had been hit by friendly anti-aircraft fire. Anthony Fokker feared that with the death of this popular hero, he would no longer be able to sell his aircraft to the German air force. He feared that he would be held responsible. He did commission an investigation, but for himself, the conclusion was already predetermined: friendly German anti-aircraft fire had been responsible. This would ensure that his aircraft remained unharmed.

Frantz Immelmann and other eyewitnesses inspected the wreckage themselves and concluded that the synchronization mechanism had clearly failed again. Immelmann had therefore shot his own propeller to pieces due to the malfunction. Just as he had done several times recently, but this time with fatal consequences. Frantz Immelmann wondered why his brother hadn't shut down his engine, as he had on May 31st. Had he perhaps been too preoccupied with the attack or avoiding opposing fire and only noticed his propeller's failure too late? Whatever the case, the German investigations raised more questions than they provided answers.

For the British, however, the cause was irrefutably established. Based on the hits on the Fokker, they maintained their conclusion that Immelmann had been killed by McCubbin and Waller's strafing runs. The photos of the wreckage of the E.III also offered no definitive answer. They only showed possible bullet holes in the tail section. The propeller, on the other hand, looked badly damaged. A blade was missing just at the root, as if it had been cut straight across. This could have been the primary cause. The strong vibration of the engine would also have shaken the fragile aircraft, causing the tail to break off and the wings to fold in half.

Max Immelmann was one of the first great flying aces to die in combat. Oswald Boelcke said of his fellow aviator's heroic death: "An accident – he shot off his own propeller! He was undefeated! How fortunate for him to have met such a swift and beautiful soldier's death." But the shock was unimaginably great, even for Wilhelm II. The German High Command had already noticed that German morale had suffered severely from Immelmann's death. In consultation with the high-ranking warlords, it was decided that the other great public air hero, Oswald Boelcke, should not be exposed to any further risks. To his great anger, Boelcke was banned from flying for a month. Ultimately, this ban was converted into a mission of observation through all the war zones. Afterward, he received the task of forming a new Jagdstaffel (fighter squadron). In September, Boelcke returned to active duty. However, this air ace was also short-lived. Barely four months later, on October 28, 1916, Oswald Boelcke was killed on the Western Front after a collision with one of his own men. This happened mid-air during a dogfight with the English and French, as he tried to avoid a French aircraft.

Just as with the repatriation of Immelmann's remains to Dresden, his funeral was also attended by a large crowd. Thousands lined the route during the state funeral. Immelmann's mother did not mourn, because, as she remarked, "see how all their thoughts are with him, and thanks to those thoughts, Max lives on!" It was a true hero's funeral in Tolkewitz. A Staffel flew overhead and a Zeppelin soared majestically over the treetops, while members of the air corps scattered roses from the gondola as a final tribute. The presence of Crown Prince Boris of Bulgaria and twenty generals at the funeral demonstrated Max Immelmann's importance to the German people. The German national anthem was played afterward. Oberleutnant Max Immelmann was buried at the Johannis-Friedhof. His body was later exhumed and cremated at the Dresden-Tolkewitz crematorium. His dog, Tyrus, remained with his mother.

Legacy

Max Immelmann has always remained an eccentric figure in the stories and legends, but he was a driven specialist in a profession he practically had to invent himself. For Max Immelmann, everything revolved around serving his country. During his final aerial combat, Immelmann did shoot down two aircraft, but he was unable to claim them himself, meaning those victories were never added to his official tally. However, Savage's FE2b was claimed by—and also awarded to—his pupil and friend Max Mulzer as his fourth victory. Mulzer had also fired on that FE2b. Yet, no one doubted that Immelmann was the true conqueror. Incidentally, Mulzer became the next pilot, after Immelmann and Boelcke, to be awarded Pour le Mérite.

Of all Immelmann's victories, only one was identified by a French aircraft. French records were not only confusing but also incomplete. All other victims were known. Max Immelmann was 25 years old when he died. His career as a fighter pilot was short but impressive, and with it, he had earned an important place in aviation history. Many Germans would never forget "their" Immelmann. A statue was designed for him by Professor Pöppelmann. On June 24, 1928, the grave monument in his honor was unveiled. The statue depicts a young man standing on the ground with a sword in his right arm, while his left arm, extended upward, follows his gaze to the sun. It is a symbolic pose of Max Immelmann's constant triumphant flights toward the realm of light. The pedestal is inscribed: Max Immelmann, der Adler von Lille.

The German composer and conductor Hermann Ludwig Blankenburg (1876-1956) also wanted to keep the memory of the young German pilot alive. Blankenburg was known as the German march king, having composed many marches. A march dedicated to Max Immelmann, entitled Der Adler von Lille (March, Op. 180), was added to this oeuvre. It is unknown whether the composer wrote the first notes during Immelmann's successes or only after his death.

The Immelmann maneuver

Max Immelmann is associated even more than Oswald Boelcke with the Fokker Eindecker, Germany's first fighter plane. Boelcke became famous for his Dicta, a treatise on air combat rules and tactics he wrote during his leave after Immelmann's tragic death. Max Immelmann became famous for the Immelmann maneuver, the most famous and important maneuver used to gain altitude. The maneuver involves the pilot performing a half-loop followed by a half-roll at apogee, thus gaining altitude and simultaneously reversing the flight direction by 180 degrees. It is not entirely certain whether Immelmann himself performed this maneuver, and if he did, whether his Fokker Eindecker could have handled it. Immelmann himself never confirmed that he performed this maneuver. It may have been named by British pilots who used it as a means to escape the feared fighter pilot.

More likely, the maneuver Immelmann performed is a

wingover The pilot lifted the nose of his Fokker as if he were going to loop the loop, but instead, he performed a vertical turn and ended up facing the opposite direction. It was a simple movement that simultaneously gained altitude and landed him facing the opposite direction.

Consequences for Fokker

For Anthony Fokker, the death of Max Immelmann meant a temporary reduction in aircraft deliveries, despite his own research. The German pilots, however, proved to be less than enthusiastic fans of the Fokker Eindeckers. They could not compete with the new, more efficient enemy fighters. Moreover, the E.IV was inferior to the E.III. The twin-row rotary engine meant double the weight, making the aircraft more difficult to maneuver. Moreover, the engine became less reliable after just a few hours. While the E.IV suffered from double the unreliability, it did not deliver the expected double the performance. The new successors, the biplanes D.I. through D.IV., initially equipped with Mercedes engines and later with the more powerful BMW engines, were also substandard. They were merely filler aircraft until competitors Karl Thies and Albatros Flugzeugwerke launched the far superior German fighters, the Halberstadt and Albatros, respectively, in September 1916. The German pilots were eager to fly these aircraft. It wasn't until late 1917 that Antony Fokker regained some of his good standing by introducing his Fokker Dr.I Dreidecker. In 1918, he astonished the world with the success of his sublime Fokker D.VII.

List of medals

- Iron Cross, First Class, 1 August 1915, after his first victory

- Iron Cross, Second Class, 3 June 1915, after flying a successful reconnaissance mission with Lt. von Teubern (observer)

- Military Order of St. Henry, Knight, September 21, 1915

- Royal House Order of Hohenzollern, Knight's Cross with Swords, November 1915

- Military Merit Order, Fourth Class, ca. 6–12 December 1915

- Pour le Mérite, January 12, 1916, after his eighth victory

- Hanseatic Cross (Hamburg), March 15, 1916, after flying anti-aircraft defense for the mayor of Hamburg

- Military Order of St. Henry, Knight Commander, March 30, 1916, after his 12th and 13th victories

- The Turkish War Medal of 1915 (Ottoman Empire), April/May 1916

- Imtiyaz Medal in Silver (Ottoman Empire), April/May 1916

- Albert Order, Knight's Cross with Swords, April 1916

- Silver Friedrich August Medal, "For Gallantry in the Face of the Enemy", July 15, 1915

Literature

- Franks, N., Dog-Fight. Aerial tactics of the aces of World War I. Barnsley, Pen & Sword Books, Ltd.

- Immelmann, F., Immelmann. “The Eagle Of Lille”. Havertown, PA, Casemate, 2009

- Immelmann, M., Meine Kampffluge. Suicide lives and suicide counts. Leipzig, Klarwelt-Verlag 2016

- Levine, J. –Fighter Heroes Of WW I. London,. Harper Collins, 2009

- Steeman, P., - Airmen of the First World War. The gesture of Guynemer. Soesterberg, Aspect, 2012

- Sykes, J.Vigilant., –German War Birds. Pennsylvania, Greenhill Books, 1988

- Vanwyngaarden, G & Dempsey, H., –Early German Aces of World War I. New York, Osprey Publishing 2006

- -Werner, Prof. J., –Knight Of Germany. Oswald Boelcke German Ace. Havertown, PA, Casemate 2009

PDFs

- Hollway, Don –The Eagle of Lille- http://www.donhollway.com/immelmann/