What about Karel Mareš?

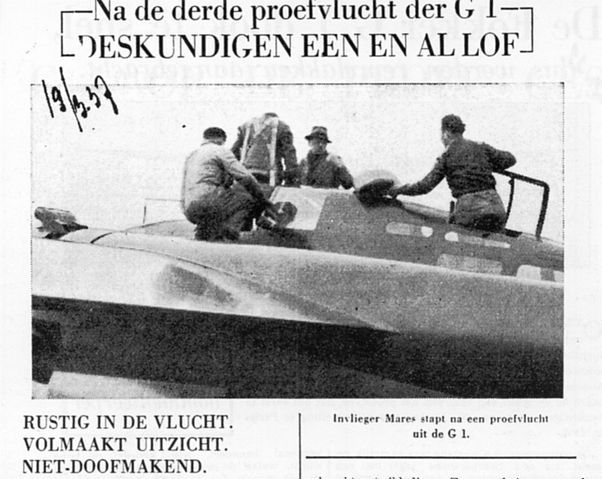

Every Dutchman knew the Fokker G.1 in 1937. But no one knew the test pilot who made the first flight and then spent four weeks putting the prototype to the test.

His name was Karel Mareš, a Czech who wasn't employed by Fokker. Why was this unknown foreigner chosen? Why were Fokker's factory pilots passed over? We still don't know.

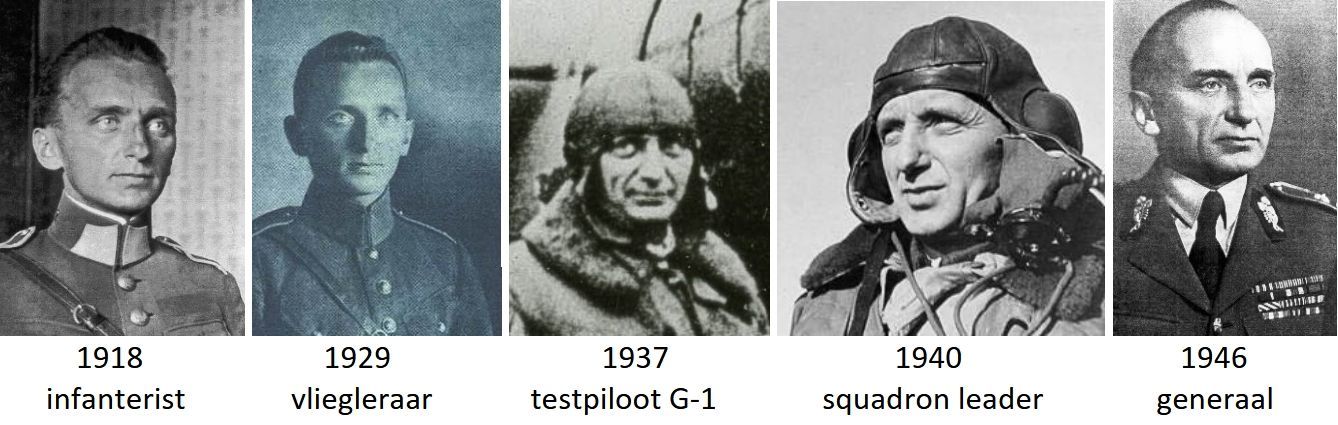

Who was this Karel Mareš, anyway? We can finally give a comprehensive answer to that last question.

For the first time we show photos where his face is clearly visible and in one of them he is standing in front of the G.1.

After 1937, Mareš never returned to the Netherlands ― his turbulent life makes clear why.

Karel Mareš (pronounced Karél Marésj) was born in the town of Tábor, about 100 km south of Prague, where he attended primary school and grammar school. The country now known as the Czech Republic was then part of Austria-Hungary, a dual monarchy that fought on the German side during World War I.

In February 1917, Mareš was called up for military service. As an 18-year-old infantryman, he fought on the Italian front in South Tyrol and rose to the rank of lieutenant.

After the First World War, Austria-Hungary disintegrated. A portion remained as Czechoslovakia, an independent republic that proved capable of building its own aircraft and soon had its own air force.

Mareš, who had continued his military career after 1918, joined the new air force in 1923. He learned to fly there and proved to be an outstanding performer. In 1927, he became an instructor at the military flight school, where he made nearly 3,000 flights with his students. Mareš also participated in international air competitions, where he achieved high scores.

In September 1936, Mareš entered service as a lieutenant colonel in the VTLÚ (Vojenský Techniký a Letecký Ústav = Military Technical and Aeronautical Institute) In Prague, a military institute was established to support the domestic industry with theoretical and practical aviation knowledge. The VTLÚ had wind tunnels, laboratories, and a test flight department. Mareš was put in charge of this department.

He had only been in this position for six months when, as an expert from the VTLÚ, he was brought to the Netherlands by the Fokker factory to test the G.1. Mareš was therefore not a factory pilot with the Czech company Avia, not an employee of Fokker, and not a freelancer, as is sometimes claimed.

Arriving in the Netherlands, Mareš single-handedly subjected the prototype of the Fokker G.1 to a full test program.

Between March 16 and April 12, 1937, that is, four weeks, he made 44 flights and stayed in the air for more than 15 hours.

According to his flight reports (written in German), the G.1 exhibited virtually no defects. Fokker was so satisfied that at the end of March, a cameraman from the Polygoon newsreel was allowed to fly along to film a report for the Dutch cinema audience.

The resulting video has been available on YouTube since 2016, but without an accompanying soundtrack. We see Mareš getting into the G.1, but his face remains unrecognizable due to the backlight.

In 1937, political tensions were palpable throughout Europe. Czechoslovakia, geographically wedged between Germany, Austria, Poland, Hungary, and Romania, was forced to rapidly modernize its air force. Czechoslovak aircraft factories were feverishly developing new fighter planes, and simultaneously, discussions were underway with England, France, and Russia regarding the possible purchase of foreign aircraft. Mareš was closely involved in both projects.

Why the Fokker factory chose Mareš over its own pilots remains unknown. Normally, a manufacturer first verifies each new product itself, corrects any defects, and then approaches potential customers.

Here it was the other way around: Fokker's own test pilots (Meinecke and Leegstra, no small boys), only got their turn when Mareš had demonstrated that the aircraft was in order.

After his last flight in the G.1, Mareš immediately left for England to make a test flight with the Bristol Blenheim.

Later, he was in Paris for a test flight in the Potez 63. Ultimately, Czechoslovakia only purchased the Russian Tupolev SB-2 abroad because it could be delivered quickly and on favorable terms. Mareš helped fly these light bombers from Kiev to Prague.

The political situation became increasingly grim. On March 13, 1938, Austria was annexed by Germany (the so-called Anschluss), causing the German threat to spread across a larger border area. That same year, six new Czechoslovak prototypes made their debut: the Aero A-300, Aero A-304, Avia B-35, Avia B-158, Letov Š-50, and ČKD Praga E-51 (which resembled the G-1, see drawing below right).

These military aircraft had to be tested and prepared for series production as quickly as possible under the supervision of the VTLÚ.

But it was already too late. On March 15, 1939, Czechoslovakia was occupied by Germany without any air force action. Germany had threatened to bomb Prague, prompting President Emil Háchat to immediately capitulate, knowing his air force would be unable to counter an attack by the Luftwaffe.

Under German authority, the Czechoslovak aircraft factories were ordered to continue construction, but now for the Luftwaffe.

The VTLÚ was also incorporated and was to continue as a branch of the German flight test centre in Berlin-Adlershof.

Mareš wasn't interested. He stayed at his post but joined the resistance, where he managed to supply the underground forces with firearms and explosives from the depot at the military airfield next to the VTLÚ.

In April 1940, Mareš was betrayed. He went into hiding and was forced to leave the country. Under the alias Karel Toman, he reached England via a long, roundabout route, where he joined his compatriots in exile.

In August 1940 he was appointed Commander in the Royal Air Force, where he commanded 311 Squadron in Norfolkth squadron that attacked Germany with Vickers Wellington bombers.

On September 23, 1940, Mareš, who signed his logbook as Toman, took part in the first attack of this Czechoslovak squadron on Berlin.

In May 1941, Mareš was transferred to London to take up a senior position in the exiled Czechoslovak Department of Defence.

In 1942, he was seconded to Russia as an envoy to help prepare for the expected liberation of his country by the Soviets. That liberation came late; the Wehrmacht only withdrew from Prague on May 8, 1945. A day later, the Red Army entered the city.

Czechoslovakia was occupied by the Germans for six years.

On February 24, 1946, Mareš returned home from Moscow; freed from the German occupiers, Czechoslovakia seemed poised to stand on its own feet again. Mareš was honored, promoted to general, and invited to various top government positions.

The euphoria didn't last long. On February 20, 1948, the communists seized power (the Prague Coup), plunging Czechoslovakia behind the Iron Curtain as a client state of the Soviet Union. Although Mareš admired the enormous contribution the Soviets had made to defeat Nazi Germany and liberate his homeland, this was too much for him. He felt unable to function within the dictatorial system and voluntarily retired on November 1, 1949.

This decision aroused suspicion in the new regime, and Mareš was subsequently kept under surveillance by the StB, Czechoslovakia's secret service.

The StB (State Security Service) deemed Mareš a dissident who was a threat to national security and had to be neutralized. And so it happened: Mareš was demoted from general to private, his war pension was withdrawn, and he was evicted from his home. He was barred from Prague. In April 1951, he was forced to find refuge on a state farm in the village of Kosovo Hora, where he was given responsibility for a manure cart drawn by a team of oxen.

His health deteriorated. He eventually had to be admitted to a hospital in Prague. He died there on June 10, 1960, at the age of 61. Karel Mareš is buried in Tábor, the town where he spent his youth.

© René Demets

This story is largely based on Czech websites translated using Google. Thanks to Bob Dros, Cor Oostveen (Fokker G-1 Foundation), Martin Smit (Aviodrome), Stanislava Moravková (Hornické Museum Příbram), and Daniel Zemam (VZLÚ).

Fokker was so pleased that at the end of March, a Polygoon newsreel cameraman was allowed to fly along to film a report for the Dutch cinema audience. The resulting film has been available on YouTube since 2016, but without the accompanying soundtrack. We see Mareš boarding the G.1, but his face remains unrecognizable due to the backlight.

Postscript

Thirty years after his death, when the Cold War was all but over in 1990, Karel Mareš was fully rehabilitated by President Václav Havel.

Posthumously, he was restored to the rank of general.

Karel Mareš is back in the spotlight in the Czech Republic. On June 10, 2015, a memorial plaque was unveiled in the hall of the school he once attended in Tábor (see photo above).

On April 21, 2018, a sculpture in the shape of a wing was installed in the garden of the Hornicke Museum in Příbram to commemorate Mareš's contribution to the victory over Nazi Germany. A park there also now bears his name.