Lipetsk, the hidden German flying school

©Annabel Junge

The Treaty of Versailles prevented Germany from building aircraft after the First World War, nor was an air force permitted.

Through a ruse, Germany managed to escape Allied surveillance and a flying school was established in Lipestk, Russia.

But how did they obtain the necessary aircraft???

INTRODUCTION

The First World War ended on June 28, 1919, with the Treaty of Versailles. This treaty imposed drastic measures on unstable Germany, where the Weimar Republic had just been established.

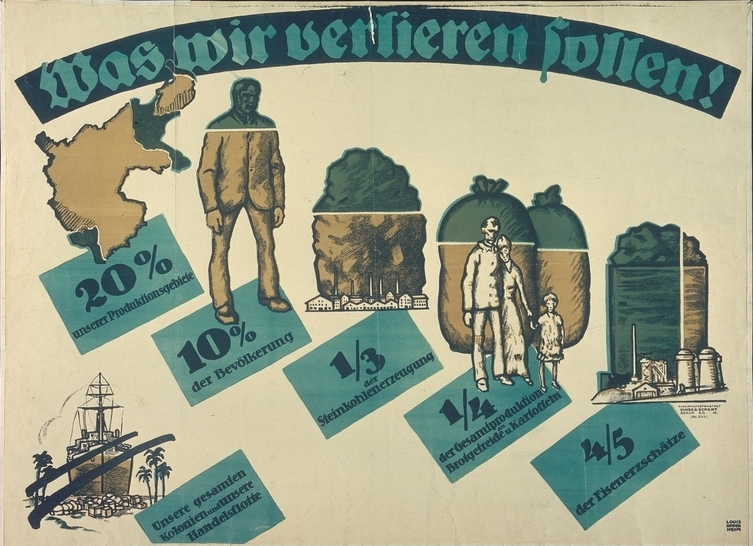

The country was thus forced to pay large reparations, was ordered to disarm completely, and all import and export of weapons was generally banned.

No tanks, no submarines, at most a professional army that could consist of a maximum of 100,000 men.

All existing warplanes were to be transferred to the Allies or destroyed.

In the short term, all imports and production of aircraft, aircraft parts, aircraft engines and components were also banned.

The treaty explicitly mentioned the German delivery of the Fokker D. VII aircraft, as this type of aircraft had proven to be far superior to the Allied aircraft in the last year of the war.

For the German air force, these measures meant the end.

Germany was also banned from re-establishing a new air force. What remained was German civil aviation, but the aircraft in that sector were not allowed to be armored or armed.

Pilot training took place at private sport pilot schools. Training for multi-engine aircraft was temporarily suspended.

The Germans experienced this treaty as a severe humiliation, while the country also found itself confronted with economic and political challenges.

From various quarters, both in Germany and abroad, particularly from the United States, signals had already emerged that this treaty would inevitably lead to a new war.

For many Germans this was a reason to once again long for their own army and air force.

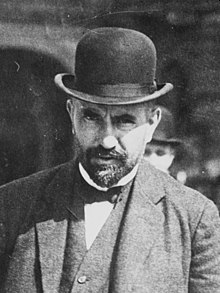

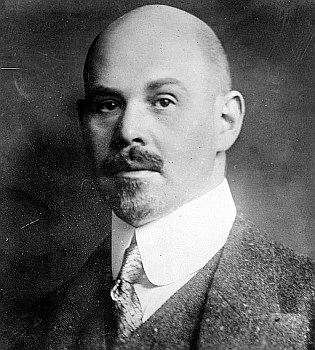

One of them was the important leader Generaloberst Johannes von Seeckt1,Commander-in-Chief of the Reichswehr from 1920 to 1926 and a Prussian soldier through and through.

He led the German military delegation that was to receive the peace treaty and the humiliation hit him particularly hard.

Von Seeckt, however, was also a man with keen political insight. He foresaw the developments that awaited the world and refused to accept the Treaty of Versailles. He felt it was necessary to restore Germany to its former military prominence. To this end, he had two objectives:

- First, he wanted a reorganization of the army within the limitations of the peace treaty, but at a level where it could be expanded into a mass popular army in a relatively short time. An air force was also necessary.

- Secondly, he wanted to preserve the strong Prussian military traditions.

It was a clear signal from Von Seeckt that he wanted to circumvent the treaty's restrictions without openly violating them. Barely a year later, Von Seeckt sought out several former officers among the pilots to make the necessary arrangements to withdraw from the treaty.

As early as July 1919, Von Seeckt had set up four small, secret and also excellently camouflaged air force units at his Truppenamt – his personal invention.

1 Johannes Friedrich Leopold von Seeckt (1866–1936) was a German general. During the interwar period, he played a prominent role in disguising German armaments and circumventing the Treaty of Versailles.

THE RUSSIANS

Everyone in Germany agreed: Germany needed to restore its national independence. The country needed to regain equal political, military, and economic standing with the other major powers.

Opinions differed on how this should be achieved. Some wanted cooperation, while others wanted to achieve this goal through rearmament.

To strengthen the German military position, a diligent search was made for new partners.

The Reichswehr held an autonomous position, allowing it to operate outside of any control by civilian authorities. This allowed the Reichswehr to operate without harming German domestic politics.

The only partner eligible for cooperation, however curious, was Russia. Von Seeckt therefore collaborated on a secret agreement with the Bolshevik authorities for German-Russian military cooperation.

Under this agreement, Germany would assist in the military training of the new Red Army and the development of the Russian arms industry.

The Russian side offered Germany the opportunity to train its own officers and build up its own armaments industry outside the purview of the Allied Disarmament Commission.

It was an agreement that would also benefit German businesses. It would even offer Germany the opportunity to secretly begin a rearmament program.

TREATY OF RAPALLO

After this secret agreement, Germany, for a better political and economic position, concluded a new treaty with Soviet Russia on April 16, 1922.

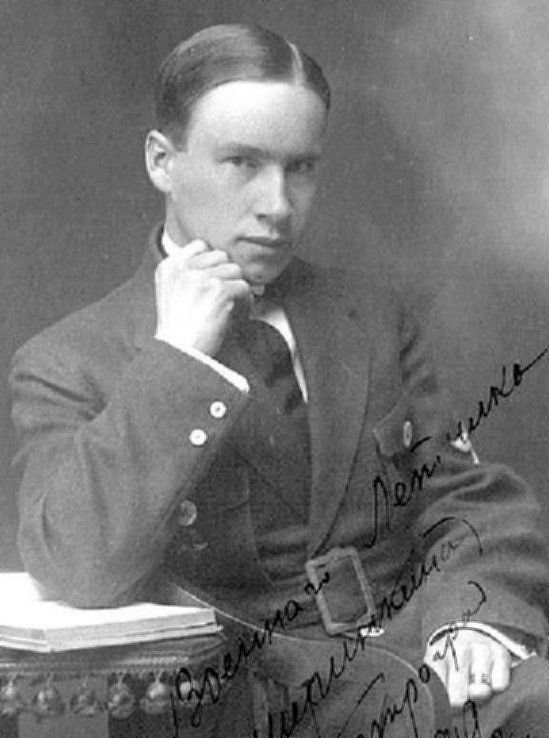

This Treaty of Rapallo came about thanks to the German Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau and the Russian People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs Georgy Chicherin.

Rathenau was actually more in favor of rapprochement with the United Kingdom. Germany was eager to reach a "settlement" with France, but because Lloyd George continued to ignore him, Rathenau ultimately opted to conclude a treaty with the Soviet Union.

In this treaty, Germany recognized the Soviet Union, which had been formed a few years earlier, and Germany relinquished all German property in the Soviet Union.

In return, the Soviet Union waived German reparations, as originally stipulated in the Treaty of Versailles.

Furthermore, both countries decided to re-establish economic relations.

The Treaty of Rapallo offered advantages to both Germany and the Soviet Union. Not only did it restore diplomatic relations between the two countries after the rupture of November 1918, it also had political consequences.

The alliance made Germany less dependent on other European powers such as France or Great Britain.

It also had a remarkable side effect. The new alliance also led to economic and military cooperation, and that alliance would have a remarkable sequel…

START MILITARY COOPERATION

Russia needed aircraft for its air force and the Germans could help with that.

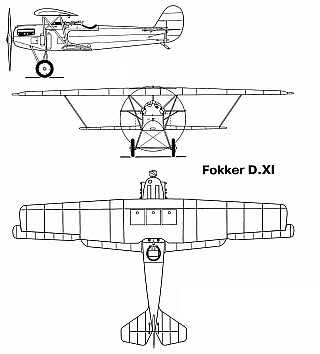

Through its trading partner in Berlin, the German industrialist and arch-conservative politician Hugo Stinnes (1870-1924), Russia placed a large order with Anthony Fokker.

Stinnes had done business with Fokker before, and in the spring of 1923 the business tycoon ordered 100 Fokker D.XI aircraft from the Dutch aircraft factory, and even suggested expanding the order to 200 aircraft.

This order became known as the "Stinnes Order." It was worth NLG 3.5 million (approximately €32 million in 2023 dollars).

FOKKER AND HIS AIRPLANES

Anthony Fokker soon suspected that Russia was the potential buyer.

Despite the attractive order, Fokker hesitated. If the aircraft were destined for Russia, trading with them would be a thorny issue for him.

On the one hand, Fokker owed a debt to the German Reichsmilitärfiskus, he allegedly embezzled four million marks in the period 1916-1918.

In addition, in 1919 he had brought several aircraft, including Germany's best fighter aircraft at the time, the Fokker D. VII, to the Netherlands by freight train.

But... he couldn't reasonably refuse such an interesting commission from a prominent German entrepreneur. On the other hand, he was back in the Netherlands, and while the Netherlands might be neutral, it didn't recognize the Soviet Union and didn't maintain diplomatic relations with the communist regime that had seized power in 1917.

Another factor that weighed against Anthony Fokker personally was the attention he had attracted from the intelligence services a year earlier due to the sale of 50 D.VII fighters, 3 C.I reconnaissance aircraft and 12 C.IIIs to Moscow.

The Soviets and Fokker met in Berlin and the Netherlands. In 1923–25, an entire team of Soviets, serving in the Red Air Fleet, even lived in Amsterdam as inspectors to oversee the construction of the D.XI and C.IV.

By the summer of 1923, talks between Stinnes and Fokker had progressed to the point where the aircraft manufacturer finally dared to enter into the agreement, although Stinnes, Fokker, and the Soviets exercised great caution regarding the sale.

On 18 June, the first order was placed for 44 Fokker D.XIs, equipped with Hispano-Suiza engines, and 6 aircraft equipped with British Napier engines.

The aircraft were built in the factory in Veere, the Netherlands, far away from curious journalists.

A month later, on 14 July 1923, the D.XI was personally demonstrated by Anthony Fokker during the National Aviation Day at Schiphol, in front of over 5,000 visitors.

The same aircraft was then subjected to the skills of the Russian pilot

Alexis Schirinkin of the Red Air Fleet. This pilot was known as a phenomenal pilot who didn't shy away from impossible maneuvers, loops, and swerves.

The ordered aircraft were transported from Rotterdam to the Soviet Union on the freighter Cleopatra.

A large number of aircraft went to St. Petersburg, another part went to Odessa.

Meanwhile, just to be on the safe side, Fokker established a Dutch-Russian trading company called Nedrus, so that his trading would have legal status.

The contract with the Russians was too important to lose; after all, there was a lot of money involved. Fokker would deliver 125 D.XI aircraft at 22,500 guilders each; and 75 C.IV reconnaissance aircraft at 30,000 guilders each.1.

The total order amounted to over NLG 5 million (approximately €46 million in 2023).

Despite all due diligence, the Dutch government was forced to learn of the deal, but against all expectations the transaction was allowed to proceed unhindered.

Anthony Fokker thought he had everything arranged properly and was waiting for an invitation from the Kremlin to complete the deal, but then things unexpectedly took a different turn.

1Ultimately, 110 were built. The initial order in 1923 for 75 C.IVs was whittled down to 60. However, a second order for 50 followed in 1924.

Fokker and the Ruhr Rebellion

When the Germans realized that the Allies' earlier concerns about a breach of contract had significantly diminished, they began placing orders with German aircraft manufacturers to develop military prototypes.

They were selective in their purchases of equipment. Fighter aircraft ready for series production were not available anywhere in Germany at the time.

But even outside of that, it was not easy to obtain large numbers of devices.

For example, the factory of the German aircraft manufacturer Hugo Junkers in Fili near Moscow, where military prototypes were developed, could not deliver several aircraft until early 1924 at the earliest.

So the attention shifted to two other companies, namely Heinkel and Fokker.

Ernst Heinkel had just established his Heinkel-Flugzeugwerke. Delivering large numbers of aircraft quickly wasn't yet possible for him.

Fokker, however, was able to deliver a series of aircraft in a short timeframe. But he had squandered his good name in Germany through financial misconduct and a failed partnership with Hugo Junkers.

Or was he now being offered the opportunity to make amends when an important situation demanded his cooperation...

In September 1923, Fokker was personally visited by three former German officers in plain clothes, who introduced themselves as unofficial representatives of the Ministry of War, namely Felix Wagenführ - director of Hugo Stinnes GmbH, Walter Hormel - technical employee - and Kurt Student 1- a former test pilot.

They had a simple question: whether Fokker would be willing to build and deliver another 50 D.XI aircraft to Stinnes.

They also ordered 50 aircraft of the latest type, the D.XIII. With its 570-hp Napier Lion engine, this model was the fastest fighter aircraft in Europe at the time and had a range of 600 km, and a maximum altitude of about 7,500 m.

They also had to be equipped with German machine guns.

It was immediately clear to Fokker2These aircraft were not intended for the Russians, but perhaps for disarmed Germany?

Civilian air traffic already existed between the Soviet Union and Germany. Deruluft, a German-Russian airline for mail, freight, and passenger services, had been operating since November 11, 1921. The first aircraft used were also Fokkers, namely the F. III and later the F.V.3.

But the negotiators involved stated convincingly that the order was intended for a subsidiary of Stinnes in Argentina.

The actual destination was the Ruhr area.

As a result of Germany's failure to pay reparations to the Allies, French and Belgian troops occupied the Ruhr area on January 11, 1923.

They seized key industrial assets as compensation for unpaid reparations.

The occupation led to a deep economic and political crisis in Germany. The revolutionary overthrow of capitalism was within reach.

It didn't stop at just one protest; a second wave quickly followed. The owners of heavy industry, led by Hugo Stinnes, financed the uprisings through the so-called Ruhr Fund.

The aircraft order was paid from that fund.

On September 26, Chancellor Gustav Stresemann (1828-1929) put a definitive end to the uprisings and the frantic emergency armament measures.

Because of the military détente that finally emerged from the Ruhr area, the Reichswehr was faced with a major problem: Where should the ordered aircraft be housed now that they were no longer needed?

This question also arose in the navy, because aircraft had also been ordered there, albeit to a considerably lesser extent.

The Reichswehr Ministry therefore developed a plan to use existing aircraft for training and education. But where could this be done?

With a partner with whom several agreements had already been concluded: Russia!

1Kurt Student (1890-1978) later became a general in the German Luftwaffe. In that capacity, he was involved in the bombing of Rotterdam in May 1940.

2 As a token of gratitude, Anthony Fokker was awarded the Iron Cross Second Class on May 7, 1924.

3

The first Deruluft F.III landed in Moscow on April 30, 1922. The remaining nine F.IIIs also flew to Moscow. This was quite unusual in those days, as it required stopovers in Hamburg, Berlin, Königsbergen, Kaunas, and Smolensk. From Königsbergen, there was virtually no infrastructure for aircraft arriving from abroad.

Lipetsk

At the behest of the People's Commissar of War, Leon Trotsky, Enver Pasha, then residing in the Soviet Union, wrote1 on August 26, 1920, a letter to Generaloberst Von Seeckt.

In it he proposed deploying German military instructors at some Red Army training institutes.

In the context of these new German-Russian relations, General Hermann von der Lieth-Thomsen undertook2in the early 1920s several trips to Moscow for negotiations.

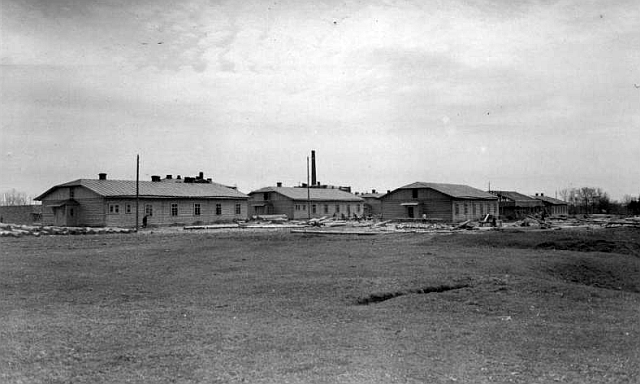

During one of these trips, the Russians made their new allies an attractive offer, one that naturally also served Russian interests: the Germans were allowed to use an airfield located on a plateau 20 km from the spa town of Lipetsk, with a population of approximately 25,000. This area belonged to the 4th Squadron of the 40th Squadron of the Red Air Fleet.

A former factory formed the heart of the facility, which was in a dilapidated and neglected state. Nevertheless, the Germans agreed to the proposal.

By the end of 1924, this base, located some 370 km from Moscow, was fully operational under the German name “Wissenschaftliche Versuchs- und Prüfanstalt für Luftfahrzeuge" (Wivupal) to camouflage its real purpose – a military air base – as German activities were closely monitored from all sides.

On the western side, any military activity on German territory was followed with suspicion by the official and unofficial bodies of the Allied control commissions.

On the eastern side of the 'Iron Curtain', great caution and restraint were also required for reasons of both foreign and domestic policy.

It was therefore necessary to closely connect all the institutions of the Lipetsk complex, including those outside Lipetsk and even outside the Soviet Union.

The Reichswehr's air organization in Russia therefore formed an inseparable internal unit with the German home organization. Both in Russia and in Germany, complete secrecy was demanded of all those involved – office staff, (aspiring) pilots, and technicians.

Even in the offices directly concerned, only those officials whose cooperation was absolutely necessary were informed.

In addition to the use of false identities, no German uniforms were worn, but Soviet uniforms without ranks or civilian clothes.

To the outside world, they worked for private companies or stayed in the Soviet Union as tourists.

To further enhance the deception, the Germans initially also wanted to use Ju-22 aircraft, as the Russians had chosen this type as the standard aircraft for the Red Air Force.

The aircraft were to be built by the Junkers branch in Fili, near Moscow. With these aircraft, German actions would go unnoticed.

But the big problem was that this aircraft hadn't yet been tested, and once it was, it turned out to be defective. When the pilot corrected the rudder at high speed, the aircraft went into a life-threatening spin.

The Germans decided to abandon the Junkers and explore other options.

Meanwhile, a diligent search for a capable leader had already begun in Berlin, and the choice fell on retired Major Walter Stahr, a former fighter squadron commander on the German-French front during World War I. Despite his political stance—he was a supporter of Hindenburg and hostile to the Soviet Union—he remained director of the Lipetsker flying school for five years. The German commander was assisted by a Russian officer who maintained contacts with the Red Army and the Red Air Force. The flying school was nicknamed "Stahr Flying School."

1 Ismail Enver Pasha (1881–1922) was an Ottoman military officer and a leader of the Young Turk Revolution of 1908. He became the paramount leader of the Ottoman Empire in both the Balkan Wars and World War I.

2 Hermann Lieth-Thomsen (1867 – 1942) was chief of field aviation from March 1915 and chief of staff to the commanding general of the air force from November 1916. From 1925 until his departure due to illness in 1928, he headed the German military mission in Moscow ('Zentrale Moskou' - ZMo), which had come into operation in February 1923.

THE AIRPORT IN OPERATION

The year 1924 was designated within the Reichswehrfliegertruppe as the actual year of its founding.

At that time, the flying school consisted of a staff, a group of flight instructors, and a training squadron for fighter pilots. From mid-1924, seven German advisors and instructors also worked for the Red Air Fleet, "Gruppe Fiebig."

That year also saw the actual start of the construction and expansion of the air base, which needed to be significantly expanded to enable flight operations.

Adjusting the terrain would still pose significant challenges for the Germans, as everything had to be done in the utmost secrecy. This wasn't so true for the building materials, although the vast majority were imported from Germany.

The Russians only supplied the raw building materials such as stone and wood.

It was a completely different story when it came to transporting training and testing equipment from Germany to Russia and back, because over the years the air base also grew in terms of aircraft.

These transports had a clear military character which caused problems with camouflage.

The control of these transports therefore became a particularly complex problem in connection with the political and traffic circumstances.

Polish territory and airspace had to be avoided at all times. After all, Poland was a political enemy at the time, and the Polish military authorities were astute enough to become suspicious of what the Germans were up to. Air transport was only considered for occasional shipments of particularly valuable goods, as there was no real airspace available for air transport.

Initially, the aircraft were flown at maximum altitudes and without landings for training and testing.

On April 15, 1925, the German-Russian talks resulted in the secret Lipetsk Treaty.

It stipulated that Germany could conduct military training in Russia with complete freedom of air movement. Furthermore, the Germans were permitted to establish armaments factories where war materiel could be experimented with. Prototypes could also be freely tested there.

The conditions were that the German flight school had direct connections with the existing Red Air Fleet institutions, that the Russians were given the right to fly the German prototypes, and that technical knowledge was shared.

From that moment on, an actual test center was established in Lipetsk and the Reichswehr was able to build up a small air fleet.

On the advice of Major Stahr, the Reichsministerium decided to transfer the fifty FDXIII to Lipetsk, as they were no longer needed in the Ruhr area.

A few months later, the first Fokker D.XIIIs arrived in Lipetsk. On 28 May 1925, the steamship Edmund Hugo Stinnes 4, a freighter of the Hugo Stinnes Schiffahrt, accompanied by officers of the Truppenamt, left the port of Stettin with the 50 crated FD XIII machines on board, bound for Leningrad. This was possibly done in a single crate measuring 11.95 x 2.50 x 1.65 m, or in two crates: one measuring 7.80 x 2.45 x 1.65 m for the fuselage, and another measuring 11.30 x 1.45 x 2.30 m for the wings. In one case, each crate weighed 3,400 kg, in the other cases 2,500 kg and 2,700 kg. From there, the aircraft were transported by rail by the Red Air Fleet to Lipetsk. The costs were covered by headquarters in Moscow.

Just over a week after the planes arrived, the first group, consisting of six German staff members, including headmaster Stahr and retired flight instructor Lieutenant Werner Junck, arrived. A second group, including Karl-August v. Schoenebeck, arrived.

and test pilot Hans Leutert followed in July; observer Captain Hugo Sperrle arrived in mid-August. Approximately seventy permanently present Germans formed the core of the crew.

Now, pilot training could actually begin at the new air base. Previously, it had primarily been Reichswehr officers who had flown until 1918 and who now came to Lipetsk to refresh their flying skills. Training was now also open to Reichswehr officers with a civilian pilot's license and to future officers. The goal in Lipetsk was to train ten fighter pilots annually. This was a reasonable number for the time, as training was not possible in Germany. Thanks to the skilled German instructors, the pilots quickly became familiar with their new aircraft.

But not only German flight students received their training in Lipetsk. Numerous Russian flight students and technicians were also instructed at the air base. It soon became apparent that the Russians were a quick learner. The Russian experts were very interested observers who demonstrated an astonishing mastery of individual technical areas. These pilots, who always described their own aircraft as simple machines designed for simple people, indeed flew the German prototypes as if it were their daily work after brief technical instructions.

However interested the Russians were in German technical knowledge, they never commented on the impressions they had gained, neither positive nor negative. They carefully avoided showing surprise, amazement, recognition, doubt, rejection, and similar subjective opinions through posture or facial expressions. In this way, the Russian side gained complete insight into German technology. The reports were supplemented by Russian personnel working day and night in German factories. The boundaries between official interest and unofficial orientation blurred. Nevertheless, despite all the agreements and collaborations, the Germans tried to maintain strict secrecy, and not only from the outside world. The Germans also remained extremely cautious about sharing their knowledge with the Russians, to the increasing annoyance of the Soviets. Some highly sensitive German technology was never transferred to Lipetsk for testing, such as wireless photo transmission, a development that allowed photographs to be sent directly from reconnaissance aircraft to a ground-based receiving station.

Although the new Paris Air Agreement, signed in May 1926, allowed the resumption of distinctive fighter aircraft construction, military aviation remained prohibited. Only six pilots were permitted to be trained. From 1931 onward, that number would be reduced to three. Lipetsk Air Base remained an important training center.

From June 1926, Lipetsk had more aircraft types than just Fokkers. The first aircraft to arrive were the Heinkels, the HD 17 two-seaters, which reinforced the air base. Junkers and Albatros soon followed. Thanks to rapid progress, two complete fighter squadrons of nine German and nine Russian aircraft were soon able to engage in mock combat, leading to regular competition flights between the allies. This practice provided tactical maneuver training that would later become part of the daily routine of German fighter defenses during World War II.

Due to the growth of the airfield, the number of aircraft also grew to a total of 100 aircraft. Of these, 52 aircraft were available, of which 34 airworthy Fokker D. XIIIs and Fokker D.VIIs. For training and reconnaissance flights, 8 HD 17 aircraft and 12 Albatros types L 76 – 78 were used. In 1929, this number had increased to 43 Fokker D.XIIIs, 2 Fokker D.VIIs, 6 HD 17s, 6 Albatros L 78s, 1 HD 21, and a Ju A 20 and Ju F 13. These aircraft continued to fly until 1933.

However, since 100 Fokker aircraft, whether operational or not, were too many for a flying school, the German management decided in mid-1925 to sell 50 of the outdated Fokker D.XIs abroad.1 The aircraft were sold to Romania for over 1.4 million guilders. This money allowed the Lipetsk project to continue to be financed, as the proper functioning of the air base required a considerable investment. The Reichswehrministerium had already allocated 600,000 rubles to the flying school, of which 400,000 rubles were spent on buildings for living quarters, washing, and cooking facilities. But these sums didn't stop there. Between April and May 1927, another 560,000 rubles were invested in buildings alone, so that a year later the flying school had finally reached its full size. And it had to be said, the complex was impressive. It contained five large aircraft hangars, five staff housing blocks, and seven blocks serving as accommodation for the trainee pilots. (Three more blocks were later added). There was a large casino; a workshop, two engine test bays; a fuel station; an excellently functioning telephone exchange and radio communications, which were primarily necessary for contact with the ZMo (the ZMo). a medical facility, a library, and a bunker-like building for weapons testing. In 1929, Lipetsk's annual budget reached nearly 4 million Reichsmarks.

By the spring of 1928, the organization had grown to four sections: a staff group, the fighter pilot group, the observation group, and the weapons development research group.

The first group, consisting of 60 to 70 personnel, remained in Lipetsk year-round, as did the regular pilots who completed their training during the winter months. The other three groups stayed at the flight school only during the summer months. These included ten trainee fighter pilots, thirty trainee observers, and fifty to one hundred members of the test detachment. A variety of Russian personnel were active in all groups. In the staff group alone, for every 35 Germans, over 267 Russians were employed, including both technical and office staff.

That same year, observer training also began, aiming for at least thirteen fully functional observers per year. Technical flight exercises were also taught. Meanwhile, the Russians themselves also began providing instruction. For example, observer training began at the Russian Voronezh air base.

On September 9, 1931, German-Russian cooperation reached its peak, despite Russian espionage. A growing number of arriving goods appeared to have been deliberately damaged. This also applied to goods already in storage. The Germans' suspicions regarding Russian espionage were confirmed around the early 1930s, as every Soviet team of technicians arriving at the air base had modern, albeit incomplete, Soviet aircraft designs at their disposal. In turn, the Russians, however, revealed little to the Germans about their latest aircraft. Consequently, when Germany regained greater military freedom thanks to the aviation agreements, the observer training program was transferred from Lipetsk to Braunschweig. This relocation upset the Russians, who were already dissatisfied with the Germans' lack of openness about their military developments. Therefore, it was decided to expand the fighter pilot training program in Lipetsk. As a result, the air base experienced a peak year, with German strength rising to a total of 300 men in 1931.

In Germany itself, 3,000 people were working in the aircraft industry that same year. By 1933, this number had grown to 2,000,000 workers. Among them were people involved in the construction of airfields and factories.

1According to Dutch newspapers from the time, Fokker received an urgent order from Romania to deliver fighter aircraft as quickly as possible. If this couldn't be done very quickly, the order went to someone else. At that moment, 50 D.XIs, already paid for, were ready for Stinnes, packed in transport crates. Fokker then bought these D.XIs back from Stinnes for a considerably higher price than Stinnes had paid. This higher price was passed on to Romania.

THE END IN SIGHT

The increasing political change from the early 1930s onwards led to the base's demise. This began in 1931 with the Soviet Union's opening to the West, which led to the neutrality and non-aggression agreement with France and Poland in 1932. This agreement significantly undermined the Treaty of Rapallo. Furthermore, German plans for rapprochement with France in the summer of 1932 were added to this. These negative developments for the air base were exacerbated by the Soviet Union's considerable displeasure with its subordinate position in Lipetsk. When Germany's military equality was recognized at the Geneva Disarmament Conference in December 1932, Lipetsk ultimately became redundant from the Reichswehr's perspective.

On April 27, 1933, the Reich Commission for Aviation was reorganized into the Reich Ministry of Aviation (RLM). This marked the beginning of an independently operating military aviation sector. Initially, German military leaders believed that, after the Nazis seized power at the end of January 1933, they would be able to continue their activities in the Soviet Union unhindered for a while. But this was a grave misconception. In the summer of 1933, Hitler personally ordered the termination of cooperation with the Russians in all remaining military matters. Two months of negotiations led to an agreement acceptable to both parties. The Russians agreed that all military equipment that could be transported, either whole or in parts, by train or truck would be transported to Germany. In return, the German side agreed that Lipetsk would be transferred in its entirety to the Red Air Force. Meanwhile, the remaining prototypes were dismantled and prepared for deportation.

The remaining training aircraft, fifty Fokker fighters and twelve Heinkel training aircraft, which had already seen their best days and whose dismantling was no longer economically justifiable, were to be taken over by the Russians along with the base. On August 18, the airbase was handed over to the Russians. An outwardly solemn event, as the camaraderie typical of pilots was gone. On September 15, 1933, German relations in Lipetsk were finally and definitively severed.

Between 1924 and 1933, the air base trained 120 fighter pilots, 100 observers, and 220 ground crew members. These personnel were then used for training in the Reichswehr and, from 1935 onward, were available to the newly formed Luftwaffe as experienced instructors. The pilots were so thoroughly trained that they could later handle each new, unfamiliar fighter aircraft only after a few technical adjustments.

The trained pilots included thirty World War I pilots and twenty civilian pilots. Several naval aviators were also retrained as fighter pilots in Lipetsk. Many pilots trained in Lipetsk flew their first missions during the Spanish Civil War and built their careers there.

The activity in Lipetsk also led to aircraft innovations, such as the development of the Heinkel He 45 and He 46 as reconnaissance aircraft, and from 1932 the selection for series production of the Domier Do 11 as a medium bomber, as it was controversial due to its poor flight performance.

FINALLY

After the closure of the German school in 1933, German pilots were temporarily trained and educated at Italian schools. In addition to the aviation school and test site in Lipetsk, two other German institutions were active in the Soviet Union: a tank school in Kazan ('Kama'), established on paper in December 1926 but operational from 1929. Approximately 30 tank specialists were trained there until 1933, and a gas test site in Volsk ('Tomka'), a research and testing facility for gas warfare that operated from 1928 to 1931. Of all the secret bases, Lipetsk was the largest and most important. Secrecy was maintained until 1932, when the British ambassador in Berlin reported that the Reichswehr maintained close technical contact with the Red Army.1 By the end of 1933, the French were also aware of the existence of the Lipetsk project.

In Lipetsk, the Jagdfliegervorschrift (Jagdflieger Regulation) and the Vorschrift für Artillerie-Flieger (Artillery Regulation) were established. The designation Jabo (short for Jagdbomber) also originated during this period, when it became clear that, after a minor technical modification, a number of Fokker fighter aircraft could also be used as light bombers. During the German period, the German-Russian air base experienced only three aircraft accidents with fatal consequences for the occupants.

Lipetsk was undoubtedly the touchstone for the Luftwaffe's later proving ground at Rechlin, and it was there that the foundation was laid for the later development of the Luftwaffe.

Today, Lipetsk remains relevant in the aviation sector, albeit in different areas. It has developed into a modern aviation and technology cluster, home to several companies active in aircraft maintenance, repair, and production.

1Article in Volkskrant, April 22, 1948.

Fountains:

- Federal Archives

Articles:

- Johnson, I. Sowing the wind: the first Soviet-German Military Pact and the origins of Worldwar II. https://waronrocks.com/2016/06

Books:

- Beauvais, H. German Secret Flight Test Centers to 1945. Bernard & Graefe Verlag, Bonn, 1998

- Dierikx, M. - Anthony Fokker, a vervlogen leven. Amsterdam, Uitgeverij Boom, 2014

- Hegener, H. Fokker - The Man and the Aircraft. Aero Publishers 1961

- Mason, H.M. The Rise of the Luftwaffe 1918-1940. Dial Press, New York City, 1975

- Nowarra, H. The Forbidden Aircraft 1921-1935. Vol. 3. Motorbuch Verlag 1980

- Sobolev, DA - German Traces in Soviet Aviation History. Hamburg, Mittler & Sohn Publishing House, 2000

- Speidel, H. - Reichswehr and Red Army. Quarterly Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 1, No. 1 (January 1953), pp. 9-45. Published by: Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag GmbH

- Zeidler, M. Reichswehr and Red Army 1920 – 1933. Munich, RR Oldenbourg Verlag 1994

New Paragraph