Who was Lyuba Golanchikova?

In 1912, Anthony Fokker, 22 years old, met a young Russian aviator.

He immediately fell in love with her and hired her as a demonstration pilot. But who was she, really?

Lyuba Golancikova was born on April 21, 1888, in Viljandi, Livonia, Estonia, then part of the Russian Empire. She was two years older than Fokker. Lyuba loved singing and dancing.

Around the age of twenty, she moved to St. Petersburg, the then capital of Russia, where she soon began performing in public with gypsy songs, a popular genre at the time.

She was discovered by an impresario who contracted her for the Villa Rodé, a theatre and restaurant that was frequented by St. Petersburg's in-crowd.

There she made a name for herself as a singer, dancer and actress under the stage name Molly Morée.

Near Villa Rodé, on the outskirts of the city, stood a horse racing track. In 1910, Russia's first aviation week was held there.

Most Russians had never seen an airplane before and the whole city turned out to witness the spectacle.

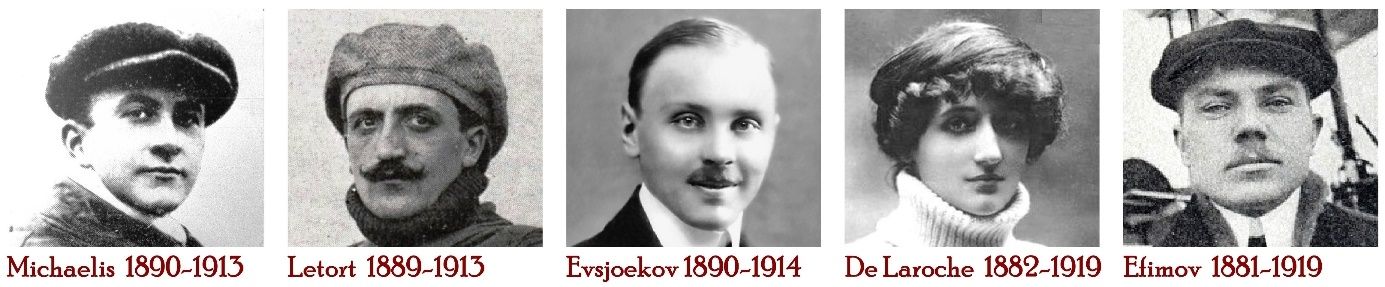

Among the participants was French actress Raymonde De Laroche, the world's first flying woman, who made a stunning impression on Lyuba.

Due to the resounding success, another flying week was organised four months later, and this time the first group of Russian pilots had their turn.

As a renowned artist, Lyuba had little trouble connecting with these flying idols. One of them, Mikhail Efimov, took her for a ride in his Farman biplane.

After this maiden flight the flying fever really struck.

A private flying school had recently opened near St. Petersburg and she immediately enrolled.

About twenty students had to work together on one plane.

The lessons were expensive and reserved exclusively for the happy few.

That is why Lyuba put aside all the money she earned during the winter of 1910-1911 so that she could start her training in the spring.

She became busy: flying lessons in the morning, rehearsals in the afternoon and performances in the evening.

Despite this, the course went smoothly; Pyotr Evshukov, her instructor, noticed she had an innate talent for flying. On October 9, 1911, she became the third Russian woman to receive her pilot's license.

In 1911, Russia saw several aviation pioneers crisscrossing the vast country, performing lucrative air shows wherever they went.

Lyuba also wanted to do something similar. But the start-up costs of this profession were enormous.

First, of course, a plane had to be purchased, and that was impossible without a sponsor. But a sponsor did arrive: a wealthy fan was willing to pay for a plane for her "because a flying woman would make him wild with love."

This frivolous offer seems to have been accepted, because shortly afterwards Lyuba terminated her contract with the theatre to perform air shows in a second-hand Farman IV.

Right from the very first attempt, in Riga, things went wrong. As she started to land and flew low over the crowd, over-enthusiastic spectators began throwing hats and walking sticks into the air. The propeller was hit, Lyuba lost control, and her biplane crashed into a fence.

The plane was damaged and Lyuba was injured. She had to temporarily suspend her flying career.

A few months later, Lyuba turned up at the flying competition in St. Petersburg in which Anthony Fokker participated.

She became interested in the Spin, which Fokker and Hilgers flew with flair. Perhaps such a maneuverable monoplane would allow her to continue her air shows.

Fokker, captivated by this attractive young woman who seemed to understand everything about airplanes, took her to Berlin. There she began intensive training on the Spin.

She proved to be so good at it that Fokker offered her a job as a demonstration pilot, realising that the charismatic Lyuba, an entertainer by nature, always attracted a lot of attention anyway.

It worked. In November 1912, she broke a women's world record by soaring to 2,400 meters in a spin.

Fokker Aeroplanbau was thus brought to publicity with resounding success.

She could have climbed even higher, but her gloves were too thin; she had to start the descent because of her numb hands.

Lyuba was Fokker's first love, but it remains unclear to what extent that love was reciprocated.

We do know that Fokker became deeply depressed when he discovered that she was increasingly seeking the company of Gustav Michaelis, his neighbor.

Michaelis, the son of a wealthy Berlin lawyer, was a flying instructor at Johannisthal. They became close, but their relationship was short-lived. In May 1913, Michaelis crashed during a practice flight and died five days later.

Lyuba was inconsolable until Léon Letort landed at Johannisthal in July 1913. This French aviation hero flew in from Paris in a new Morane-Saulnier G and had covered 920 km without a stopover. A record. Letort, who had hung around partying, managed to hook Lyuba within a few days and promised to take her to romantic Paris.

Now an impressive prize of 10,000 marks was offered to the first pilot who would fly direct from Berlin to Paris in one day.

Letort had just completed this route in reverse.

So, one would think, pull this trick again, fly back and count your winnings!

But no, instead of extra gasoline, Léon Letort loaded his new conquest into his little plane.

Apparently he was more interested in Lyuba than in 10,000 marks.

In Paris the duo received a festive welcome from flying colleagues.

Bunches of flowers were ready. One of the bouquets contained a business card from a certain Fyodor Tereshchenko, who kindly asked Lyuba to contact him.

Tereshchenko, married to a countess, was a wealthy aviation enthusiast who lived on a colossal estate near Kiev.

There he had set up a small factory from his own funds so that he could build aircraft according to his own ideas.

He bought the necessary equipment and parts in Paris, where he was a regular visitor.

Tereshchenko was not only technically proficient but also skilled in drawing, painting, piano playing, and astrology. He excelled in everything.

He came up with an interesting proposal: Lyuba could join his service as a test pilot and would be authorized to travel around Russia at the company's expense.

She thought that would be a good idea, because she started to miss her family and friends more and more.

On December 1, 1913, she signed a one-year contract with Tereshchenko.

A week later, Léon Letort died in a plane crash.

It is not known whether there is a connection between these two events.

In 1914, while Lyuba was working for Tereshchenko, the First World War broke out. Russia and Germany were now on opposing sides.

The Russian government requested Tereshchenko to build aircraft for the air force. He complied, but with the supply route for aircraft engines from France blocked, production remained at a low ebb.

In 1917, the situation became more dire. The Russian Revolution had broken out, forcing everyone belonging to the elite into a corner. Tereshchenko was forced to flee and spent the rest of his life in France as a widely respected astrologer.

Meanwhile, Lyuba had married Boris Filippov, a wealthy businessman. The couple decided to move to New York.

In America they changed their names to Boris and Luba Phillips.

Ljoeba, now Luba, continued to closely follow developments in aviation and began to make new plans with Anthony Fokker, who had also moved to America.

In 1927 she made headlines by reaching an altitude of 3,350 metres in a Fokker F-VII Trimotor (the American version of the Fokker F-VIIA/3m).

That same year, Charles Lindbergh became the first to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean.

The press reported that Luba Phillips was preparing to do the same, becoming the first woman to do so, in a Fokker aircraft, but this plan ultimately came to nothing.

She did, however, open a beauty salon in the chic Ansonia Hotel on Broadway, where she continued to work until 1942.

Business apparently went poorly, because she subsequently worked as a taxi driver in New York for several years. She died there on March 28, 1959, of kidney problems, at the age of almost 71.

Sources:

The Flying Dutchman. A.H.G. Fokker & B. Gould, pp. 104-111 (1931)

Авиатрисса. V. Semenov, Rabotnitsa No. 8, pp.18-19 (1978)

The Imperial Russian Air Service. A. Durkota, T. Darcey & V. Kulikov, p. 262 (1995)

Before Amelia - Women pilots in the early days of aviation. E.F. Lebow, pp. 95-98 (2002)

Anton HG Fokker. A. Kauther, P. Wirtz & M. Schmidt, pp. 28, 30 (2012)

Anthony Fokker - A Bygone Life. M. Dierikx, pp. 62-88 (2015)

© René Demets

With thanks to Mart Enneveer and Marc Dierikx.