The future, seen from 1934

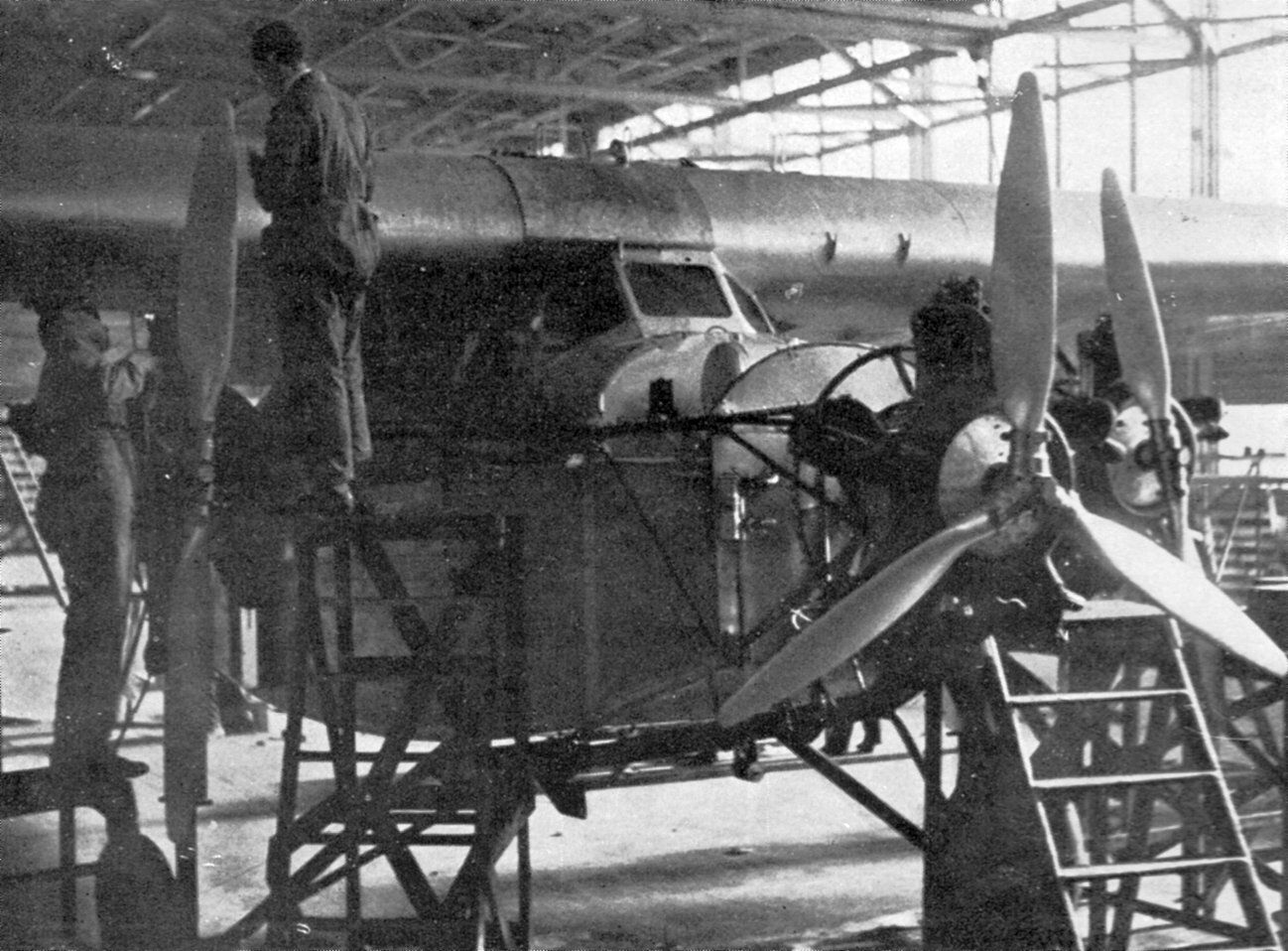

Now [1934] the journey still takes 10 days. What will the future hold? In the few years that have been in progress, significant improvements have already been made. The aircraft are becoming ever faster and more convenient. The smaller, three-engine F.VIIb has already been discontinued and the large F.XII and F.XVIII are being used, so that only large, fast aircraft with an average speed of 180 to 200 km/h are in use. The small aircraft flew at 150 to 160 km/h, and the average speed of Vander Hoop's first East Indies flight was only 120 km/h.

Along the route, ground organization has also steadily improved. Fast-operating fuel pumps, efficient telegram schedules, but above all, better airfields with hangars and wireless weather reports. The wireless system along the route has improved significantly in recent years, which is why, in early 1931, KLM gradually began equipping all aircraft with wireless stations and hiring a dedicated radio operator to operate them. While previously, ground contact was occasionally possible along the East Indies route, it is now rare for such a connection to fail. We have already mentioned the Medan bearing station. In British India (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and parts of Myanmar), there are several bearing stations, especially in the Bay of Bengal, where the monsoon is so fierce that without wireless bearing, the pilot would be at risk of losing his course. But an excellent bearing station also operates in the middle of the desert between Palestine and Baghdad, namely at the Rutbah springs. There's also a tracking station in the Mediterranean Sea near Crete. This constant connection to Earth, the organization of which is still expanding and improving daily, is one of the greatest safeguards for air traffic and also one of the means by which this traffic can proceed more regularly.

Now, while en route, you know exactly what the weather conditions are like, what the destination airport looks like, and whether rainfall has made it unusable. You also gain valuable information about tornadoes, sandstorms, and thunderstorms, which you can avoid in time, and altitude winds, which often blow in different directions, so that by flying at a certain altitude, you can often gain a tailwind.

The equipment has also improved to the extent that today's engines require much less maintenance than before. Therefore, it's not too bold to predict now [1935] that the journey time, which was recently fourteen days, then dropped to twelve, and now stands at nine or ten, will soon decrease to eight, and in the future perhaps even to seven or six. For when we discussed the European network, we pointed out the possibilities of night flights, and once all airfields along the route are equipped with adequate night lighting, and once beacons are installed between airfields, as are now the case, for example, on the route to Berlin, then it is obvious that the journey can be completed in an even shorter time. The slowest aircraft now complete their journey, under unfavorable conditions, in 89 hours, which is less than four days. The fastest aircraft are en route for 70 hours, so less than three days. If they do manage to do it in ten days, that means seven days are lost on the ground. Of course, they'll have to rest, refuel, and maintain the engines and aircraft, but of these seven days, four can certainly be made up. That leaves three days, which, together with the three currently underway, will take six days. The faster the aircraft become, the easier their maintenance, and the better the organization on the ground, the sooner this goal will be achieved.

KLM isn't sitting idle: it sees the present solely as a means to the future. All traffic to the Dutch East Indies dates back to September 1930 and is therefore still very recent. But in those few months, so much has been achieved that one has the right to look to the future with great anticipation. The fast connection between two parts of a region with such a strong commonality of interests is a must. But this fast connection is not only of Dutch importance, it is even of international importance.

We've seen how it already serves the postal interests of many nations, even those of the United States. Amsterdam-Batavia not only represents a connection between the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies, but also a connection between Europe and Asia.

For this connection, connections are already being made to the African continent, and in Cairo, there's already a connection to the British air route across Africa to the Cape of Good Hope. One link is still missing, the most obvious one: extending the line to the fifth continent, Australia. In the Dutch East Indies, the connection to the Indonesian network is guaranteed to Surabaya. From Surabaya, one can reach Wyndham in two days, connecting there to the existing network to Sydney and Melbourne. This connection hasn't yet been established, but work is underway. When one considers the Amsterdam-Batavia air route with connections to Australia and Cape Town, and subsequently also with connections to the French route to Indochina, which will soon be extended to South China, one sees that Dutch aviation has built a global route that forms, as it were, the backbone of the world's largest express connections.

The Netherlands is at the forefront of aviation nations.

Driven by the interest of our entire people, by the alertness and insight of a great nation – our own – that has always dared to tackle major challenges, something has grown that has also become the pride of our nation. Just like our magnificent shipping industry, our unparalleled Netherlands-Indies radiotelephone, something has been created for which we are envied by many nations and for which millions admire us, especially those in Asia who listen to our voices through the ether, see our blue birds come and go with the regularity of clockwork, something that is characterized by KLM's motto:

The Dutch flag is held highest in the air.

Postscript

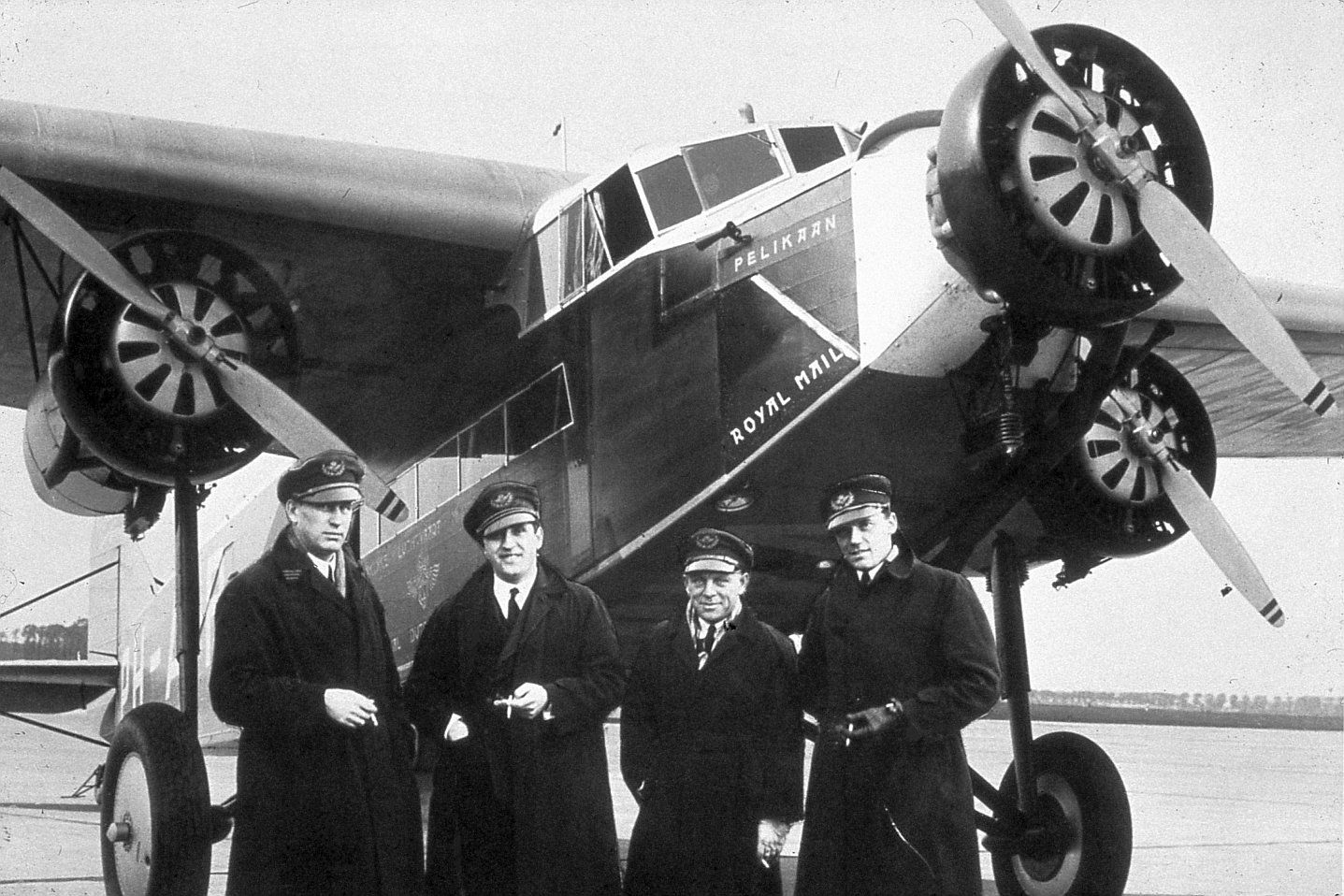

How quickly these expectations for the future have already been fulfilled, much faster than anyone in the world could have imagined, has already been demonstrated by the brilliant KLM performances of the "Pelikaan" and the "Uiver".

These tremendous flights of passenger planes, through darkness, storms, rain, and thunder, have proven that what was written above about the future just over a year ago is now, in 1935, far surpassed by reality.