Amsterdam-Batavia

Introduction

An air bridge has been built between our Dutch empire and our Asian empire, the pillars of which are KLM and the KNILM (Royal Netherlands East Indies Airlines).

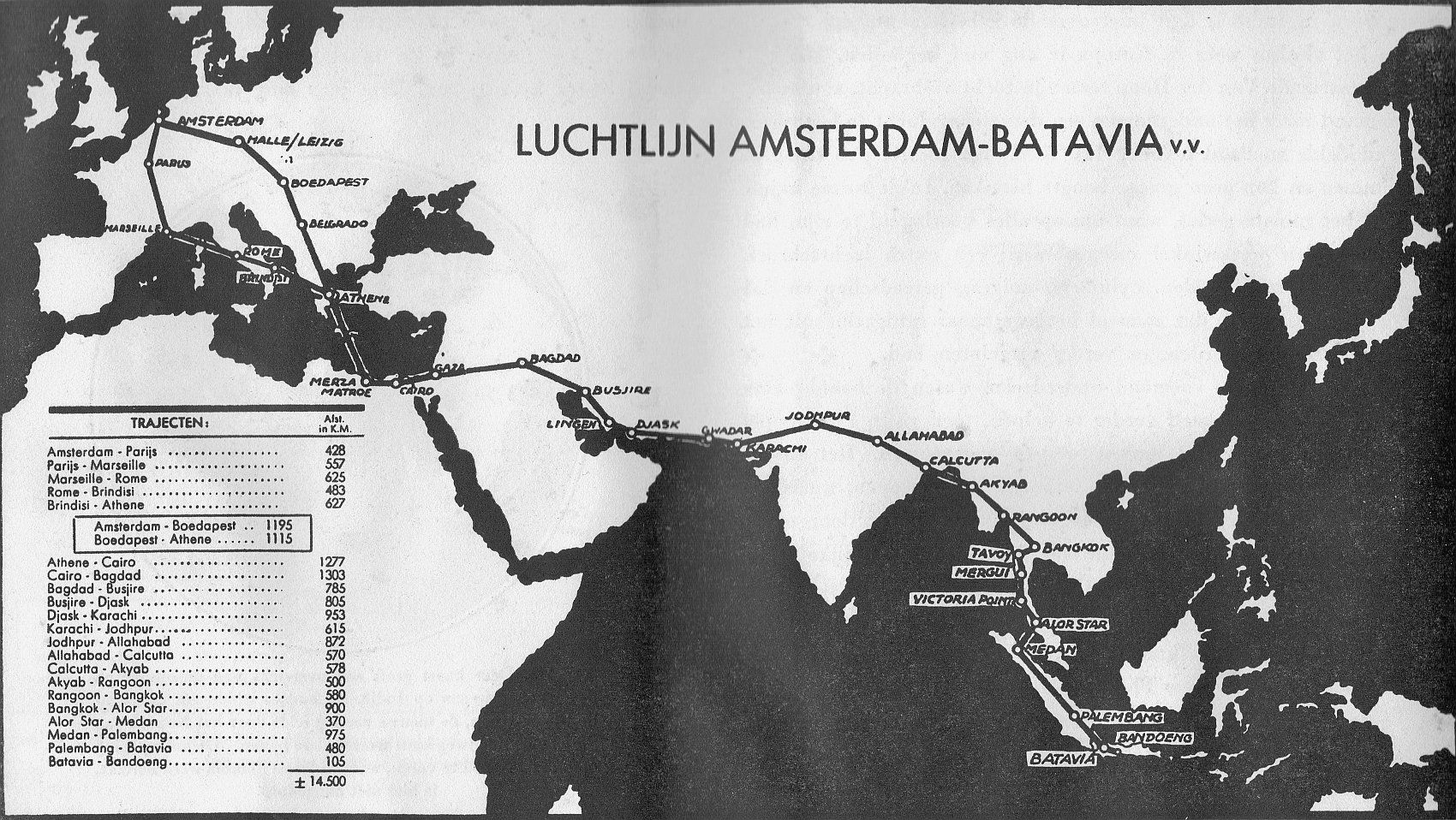

Amsterdam – Batavia, 14,350 km by air, is the longest air route in the world, flown in the shortest time, namely ten days.

Since October 1, 1931, there has been a weekly service, departing from Amsterdam every Thursday morning and from Batavia every Friday morning.

A route operated entirely differently than, for example, the British route from London to British India and the French route from Marseille to Saigon, Indochina. After all, KLM follows the procedure of flying the same aircraft with the same crew the entire way there and back.

Other companies change aircraft and crew en route.

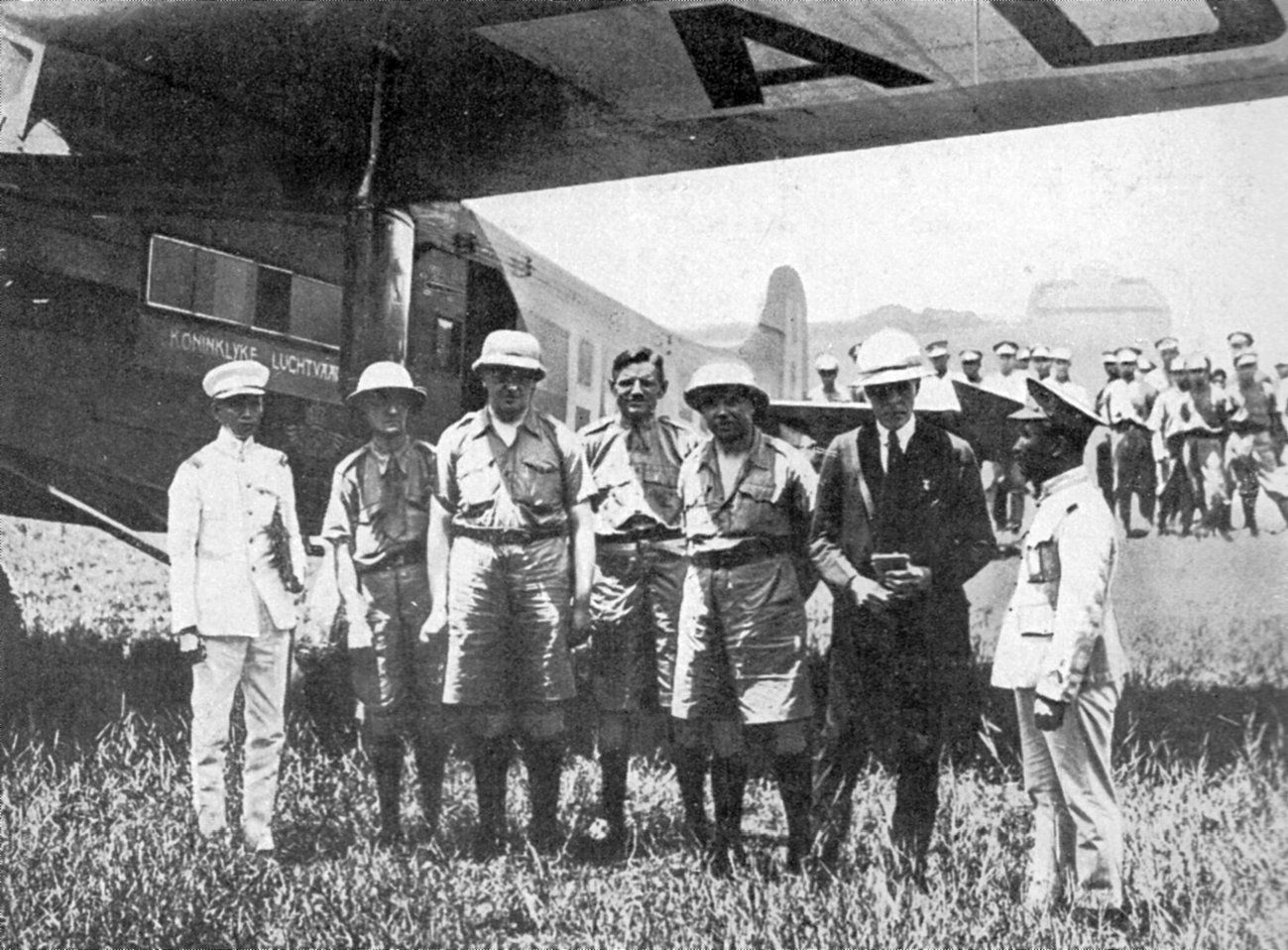

After a nine- to ten-day flight, the KLM crew arrives in the chilly, high-altitude Bandung. They have eleven to thirteen days of rest, while the aircraft is thoroughly inspected, and after nine to ten days, they return to their homeland.

This makes a total of 31 to 33 days. In five weeks, you're out and back. Just short enough to avoid tropical diseases and, especially, tropical exhaustion, taking hold of your system, and just short enough to avoid the feeling of a long separation from your family.

The Pioneers

How did this organization come into being and what was involved?

It would be a long story to describe this in detail, but in brief the development can be outlined as follows.

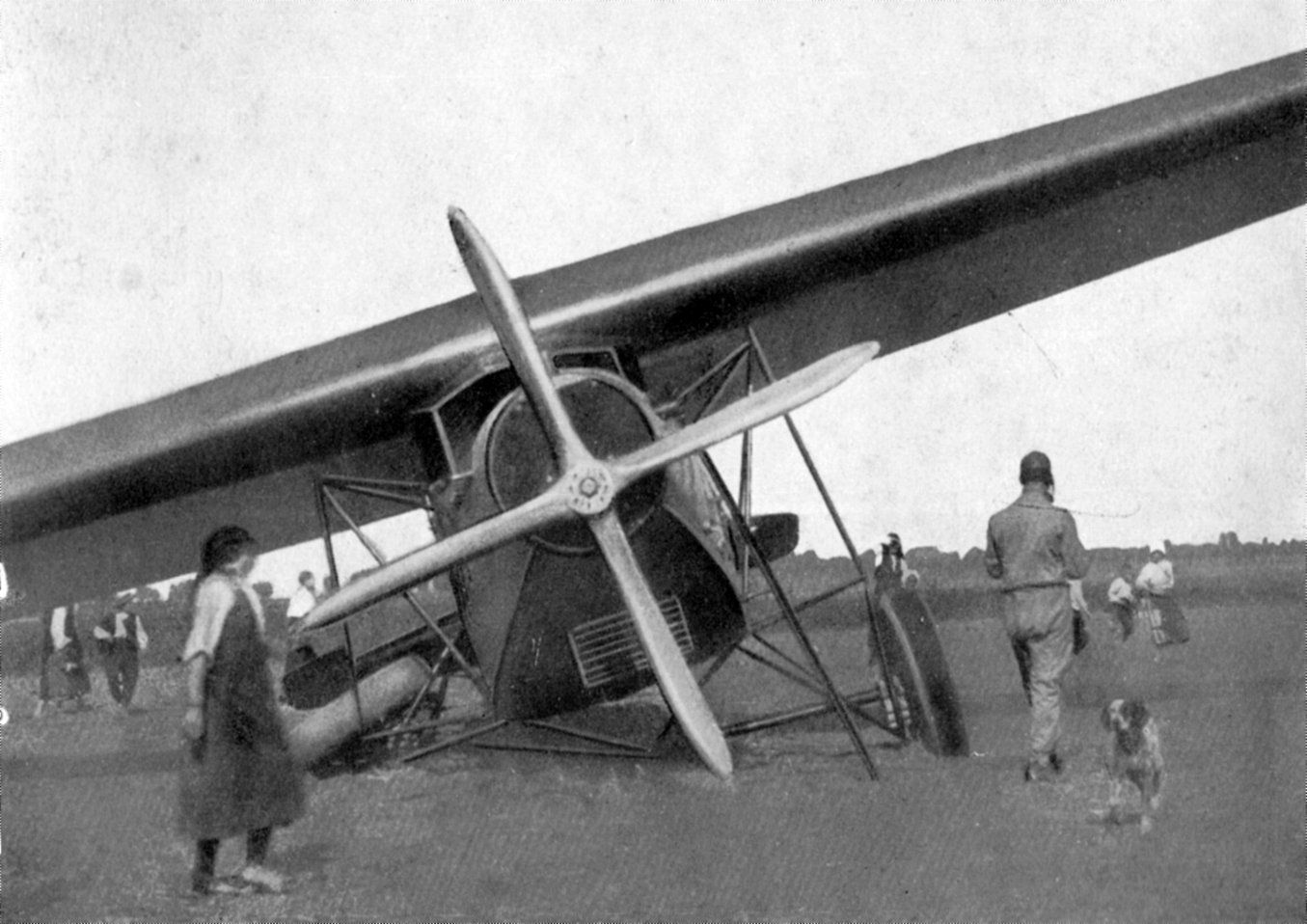

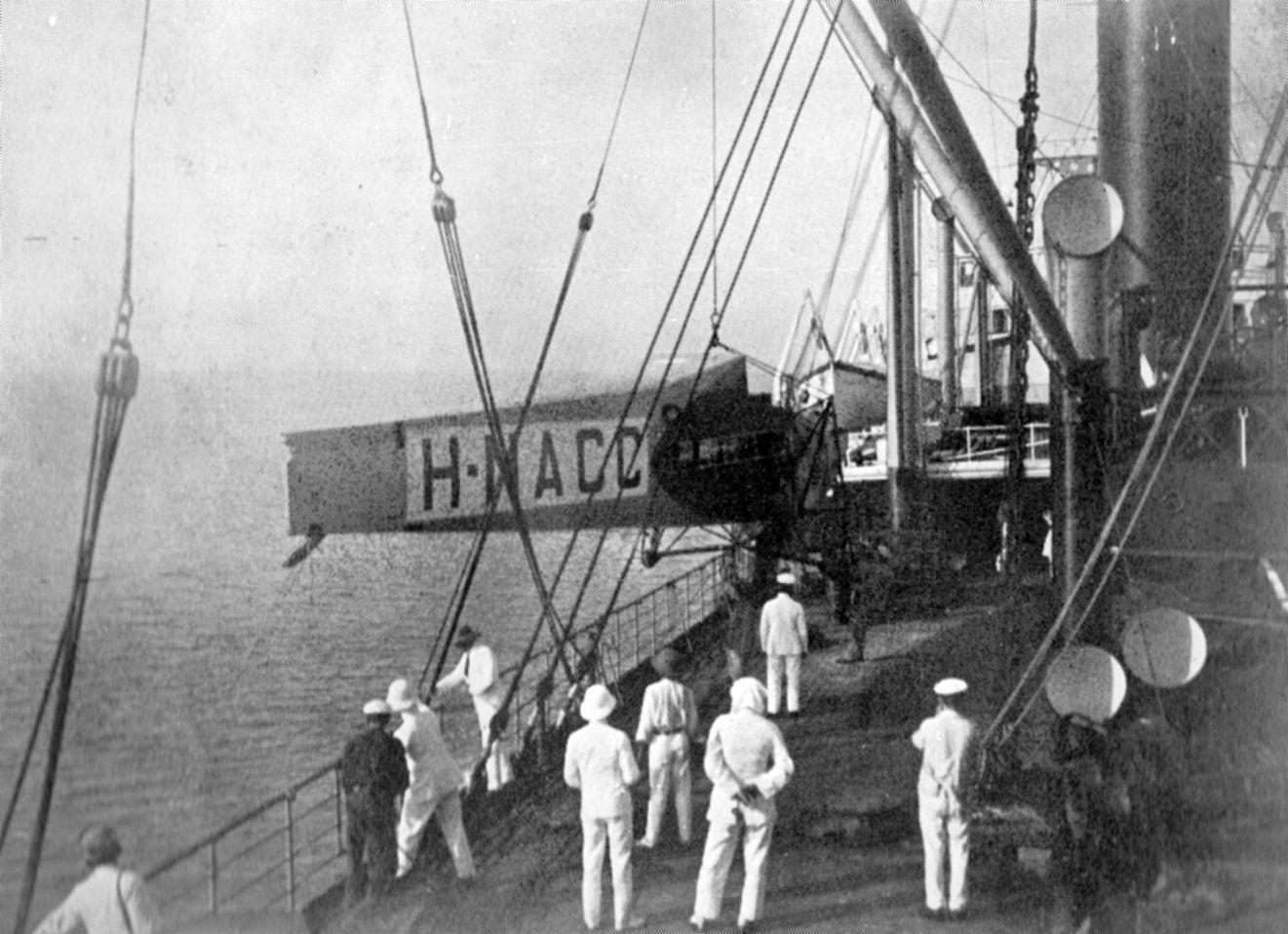

It was in 1924, on October 1, that ANJ Thomassen à Thuessink van der Hoop, leader of the tour, H. van Weerden Poelman, navigator and PAW van den Broeke, mechanic with a single-engine Fokker F VII, HNACC, equipped with a 360 hp Rolls Royce engine, began the journey via Constantinople, Aleppo, Baghdad and further along a route approximately the same as that followed today [in 1931].

The date of October 1st was carefully chosen; the monsoon in India had just ended along the entire route, and bad weather in Europe hadn't yet begun. With the aircraft Van der Hoop used to complete his flight, no one would dare attempt such a flight now [in 1935].

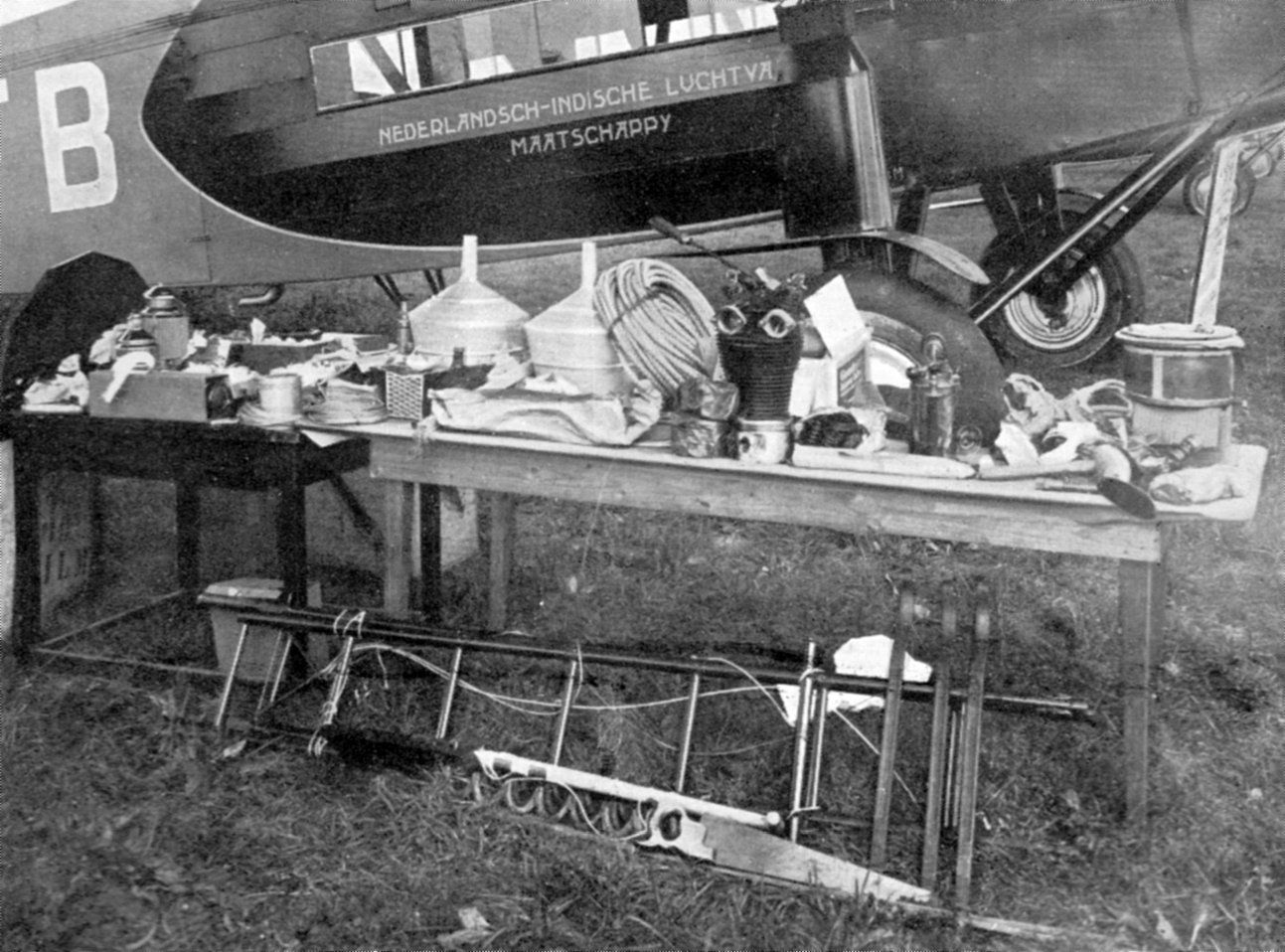

The average speed was 120 km/h, the aircraft climbed slowly, and couldn't reach great altitude. The spacious cabin offered no comfort whatsoever, as they had brought along a whole workshop to be prepared for anything: an extra propeller, an extra wheel with tires, cylinders, pistons, tools—all so heavy that everything that could possibly be spared from the aircraft had been left out.

Despite a large supply of spare parts, the pioneers were unable to help themselves when they had to make an emergency landing in Philippopel due to engine failure. It turned out that a manufacturing defect had crept into the radiator, causing a leak, a leak in the cooling water, and the engine to overheat.

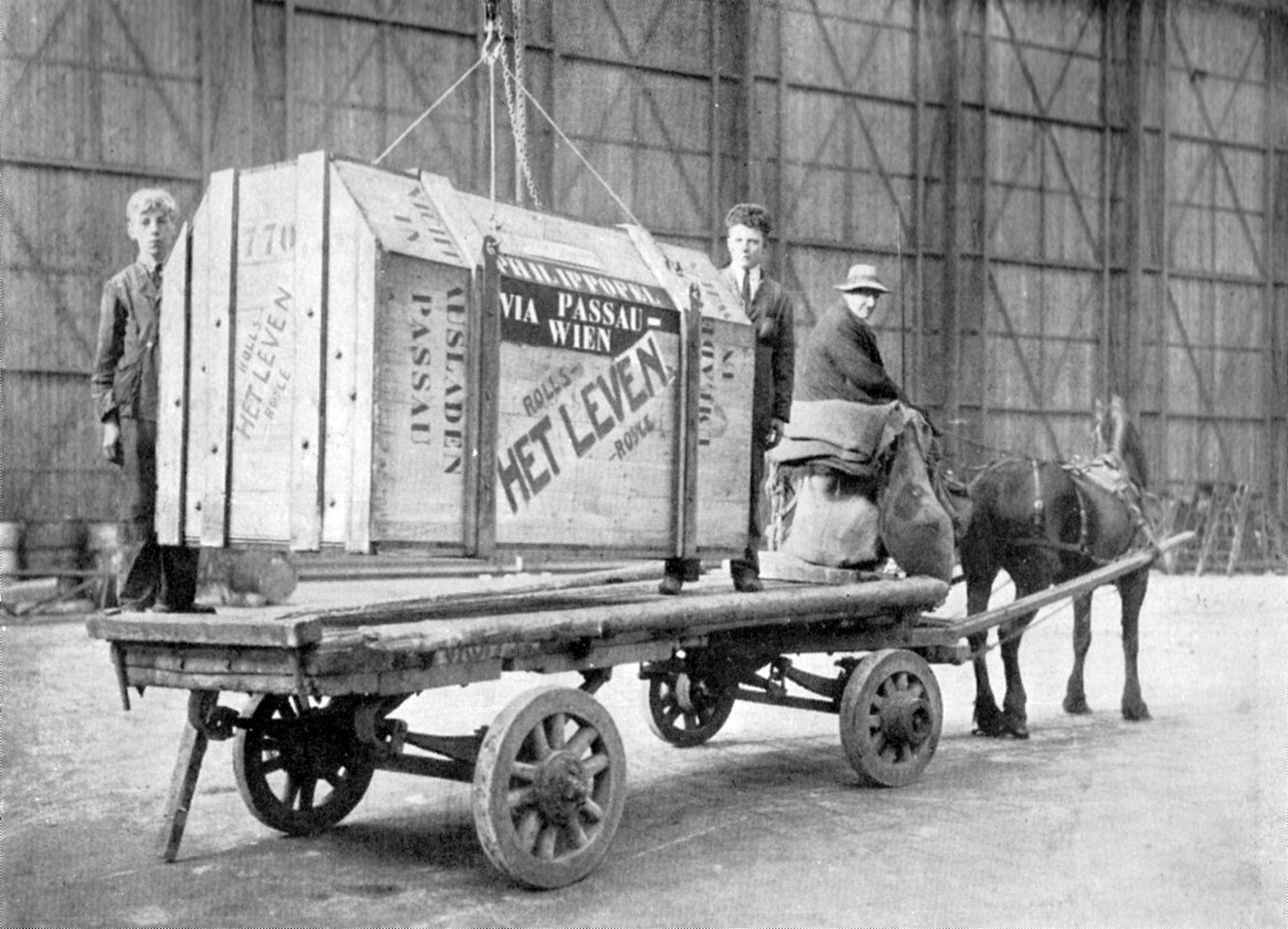

This unfortunate start would have doomed the trip. It would have remained nothing more than a futile attempt if the management of the weekly magazine "Het Leven" hadn't generously and spontaneously offered a new motorcycle.

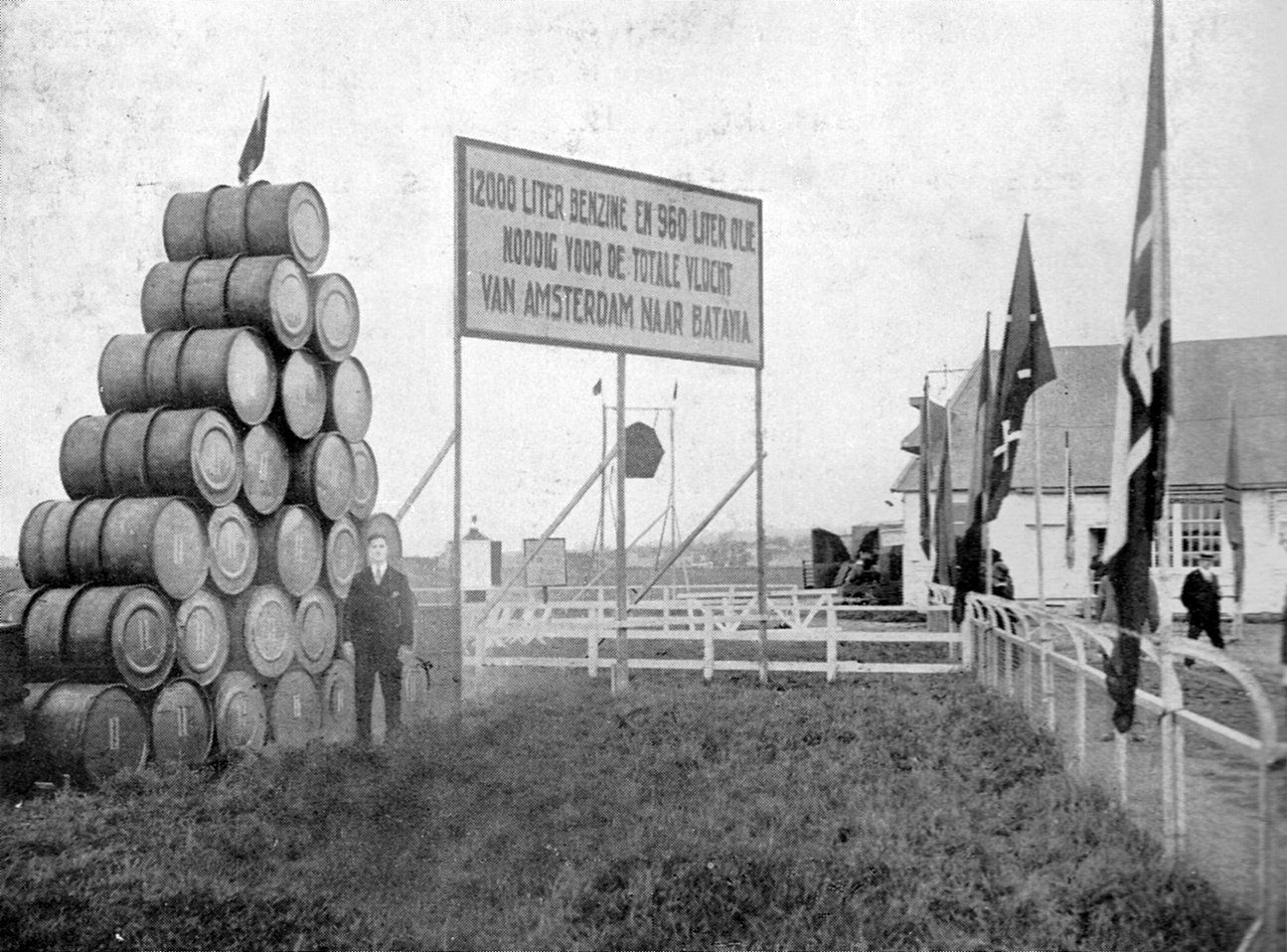

The accompanying photos show the departure of the motorcycle and an overview of the spare parts that had to be carried on the East Indies route. While not as many as Van de Hoop had with him, they were still enough to significantly reduce the payload.

Today [1935], when the route is provided with stations and workshops along the entire length, so many parts are no longer included.

The accompanying photos show the departure of the motorcycle, and below is an overview of the spare parts that had to be carried on the East Indies route. While not as many as Van de Hoop had with him, they were still enough to significantly reduce the payload.

Today [1935], when the route is provided with stations and workshops along the entire length, so many parts are no longer included.

The pioneering expedition to the Dutch East Indies, prepared with extraordinary knowledge by the then KLM pilot Thomassen à Thuessink van der Hoop, yielded a wealth of experience.

One learned the condition of the various airfields, discovered errors in the available maps, became aware of climatic difficulties, and so on.

Text continues after the photos below

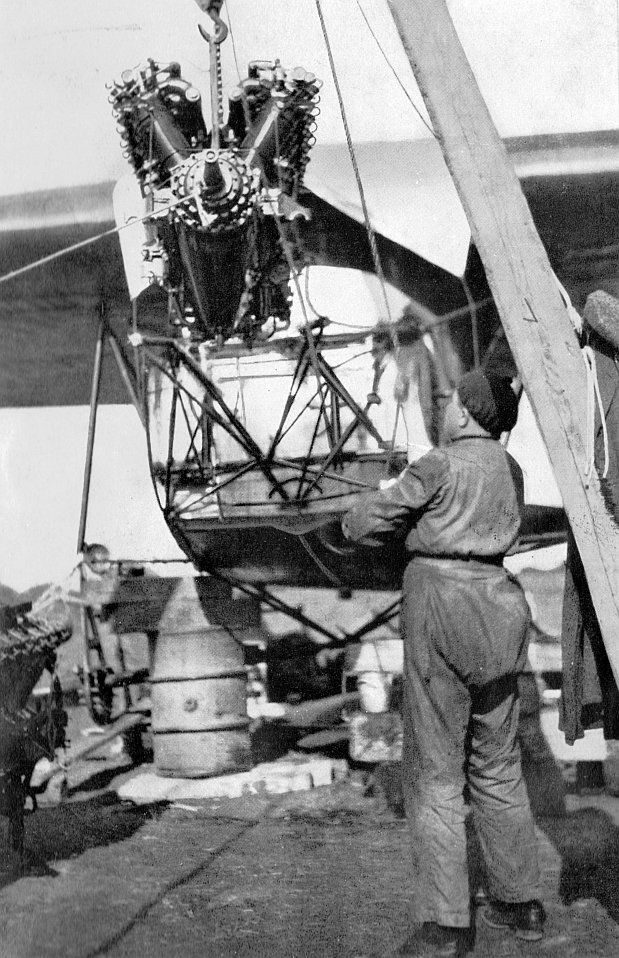

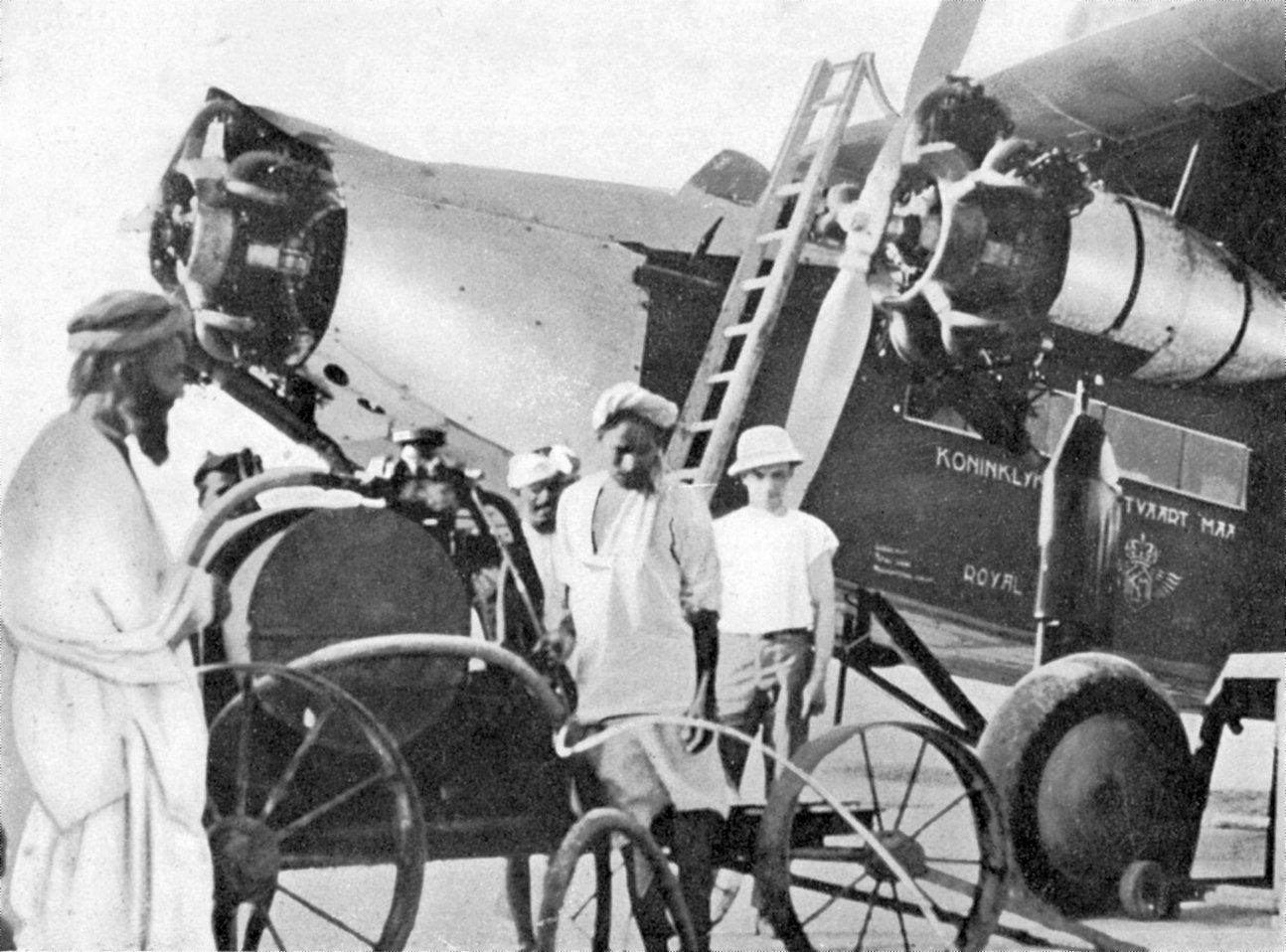

Installing the new engine. Done by Van den Broeke, the mechanic.

Van Lear Black

For three years nothing was done until the American multimillionaire Van Lear Black expressed his wish to fly to the Dutch East Indies on a KLM plane.

It was again done with a single-engine Fokker, but much better built and equipped with a more powerful engine. And indeed, the outward and return flight, piloted by Gerrit J. Geysendorfer and J. Scholte, was completed with great success in far from favorable weather conditions, as they faced heavy monsoon rains, sandstorms, and all sorts of inconveniences, which nearly ruined the flight several times.

Text continues after the photo below

The first mail flight

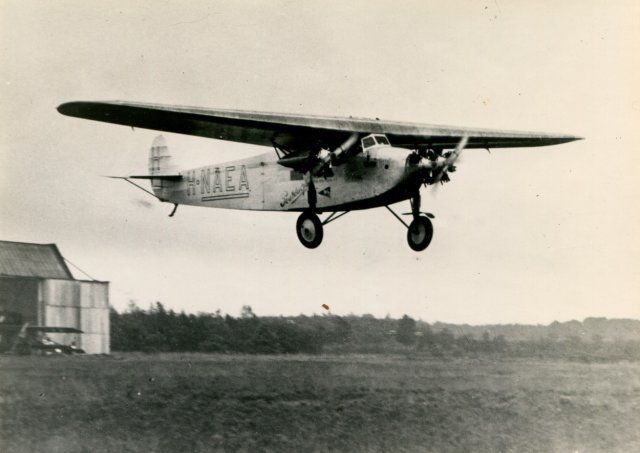

Then, in the same year and again in October, pilot GA Koppens went with his racing pigeon F VIIa H-NAEIt was the first three-engine Fokker, an aircraft built on the principle that it effectively had one engine too many, as it could remain airborne even when fully loaded on any combination of two engines.

It had one engine in the nose and one engine on each side under the wing, attached to a streamlined nacelle.

This aircraft, which also had KLM pilot GMH Frijns at the controls, completed the journey in 9 days there and 10 days back.

The organization of the Indies route

Since then, repeated test flights have taken place, this time always with three-engine Fokkers. Political difficulties repeatedly arose, hampering the continuation of the test flights, but during these flights, all the available data was collected: maps of the airfields, their location relative to the surrounding area, altitude above sea level, weather conditions, and the nature of the terrain.

Then there are the names of people qualified to represent the company's interests, a comprehensive system for supplying airplanes with gasoline and oil, a system for exchanging telegrams, a block system, like those used on railways, so that representatives in different locations can send messages to each other when an airplane has departed from a certain station but hasn't reached its destination. But also the storage of parts along the route, the plotting of courses, magnetic compass deviations, distances, and the like on maps—all of this can be described in a few words, but requires the work of many experts.

One must remember that these operations are not conducted under European conditions, and that it's not easy to find someone in a village, in a desert on the Persian coast, who understands air traffic and realizes that European speed, not Asian slowness, is required; to then obtain gasoline and oil supplies in this area, to establish a kind of weather service, and so on. The potential for such simple arrangements is beyond description.

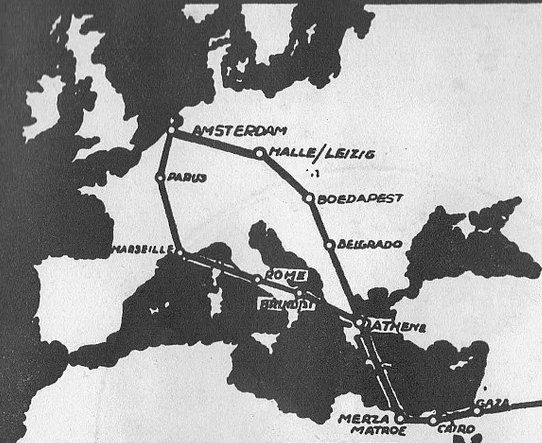

Besides Europe, the flight initially crossed Syria, Iraq, Persia (Iran), British India (India and Pakistan), Burma (Myanmar), Siam (Thailand), and the Straits (Malaysia). Everywhere, there were different regulations, different demands, and political difficulties of all kinds. Difficulties that, when the two-week service finally opened on September 25, 1930, immediately led to Turkey banning flights over its territory.

Good advice was cheap this time! KLM operated the route via Athens and Cairo, and continues to do so today [1935]. While the route was extended, it avoided the dangerous terrain of the Taurus [a high mountain range in Anatolia, Turkey], and instead, it crossed an area where a weather service already existed, several airports were located, and traffic was therefore highly reliable.

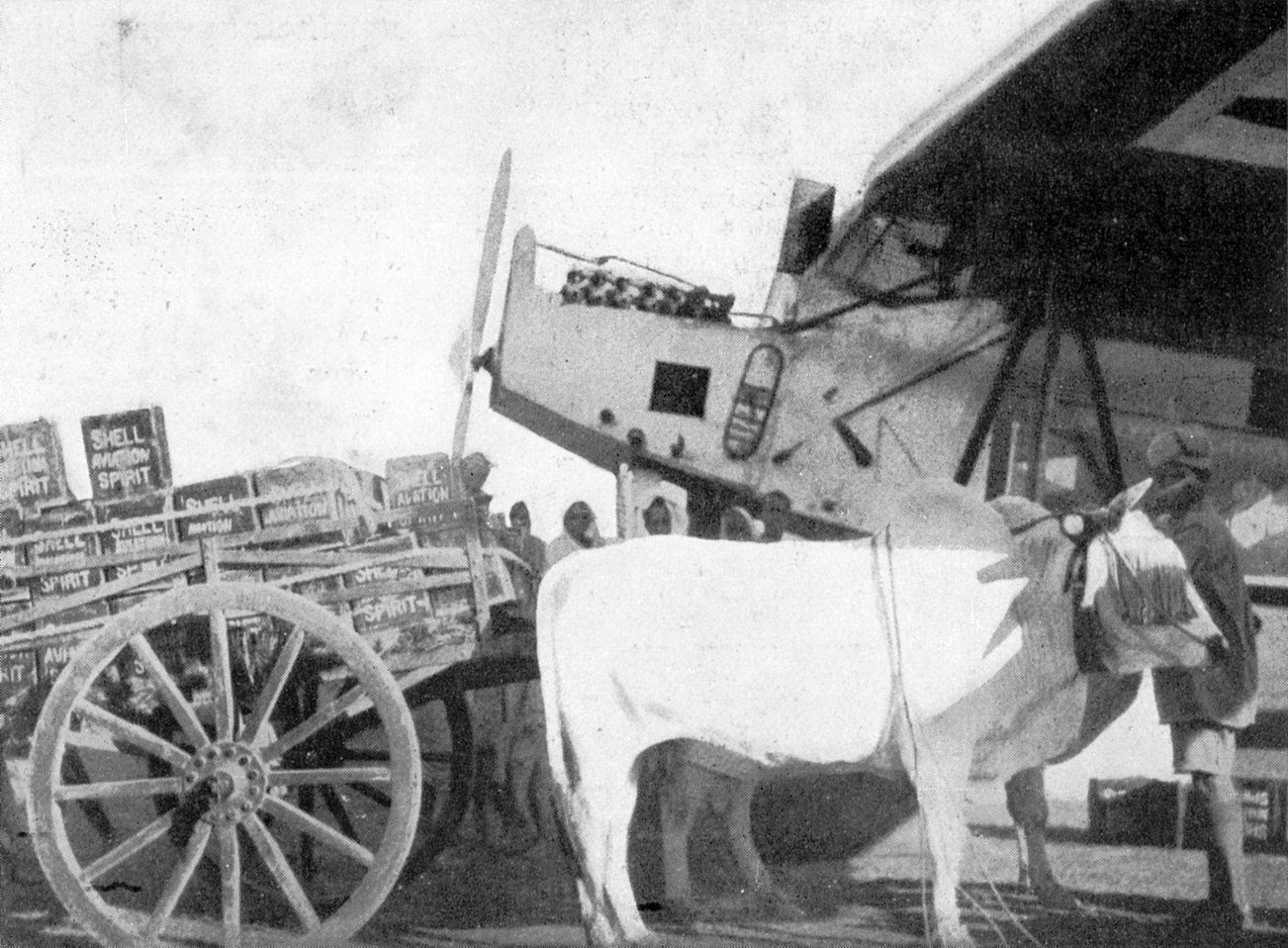

Over the years, the route's organization has steadily improved, and anyone seeing it today [1935] has a hard time imagining the primitive conditions of 1928, 1929, and even 1930. For during the first years of test flights, the pilot would land on a deserted field, and after a while, an ox cart would arrive, laden with 45 cans of gasoline, and each one had to be emptied into the wing tanks. A laborious and time-consuming task that significantly reduced the plane's speed. Now [1935] he's already forgotten those days, because when he lands, the agent is ready, and another, a representative of the gasoline company, stands with his men at a gas station; Fuel is siphoned into the wings using pumps, and what used to take hours now takes half an hour, or at most forty-five minutes. When the pilot arrives at his final destination, the plane is first filled, and then the vehicle takes him to a hotel where rooms have already been reserved for the entire crew, where their exact requirements are known, and everything is perfectly arranged. The loss of time is therefore very minimal, and that's why the average flight time, originally set at 15 days and then 12, has now shrunk to 9 days.

Supply of gasoline (SHELL AVIATION SPIRIT) at an airfield near Allahabad.

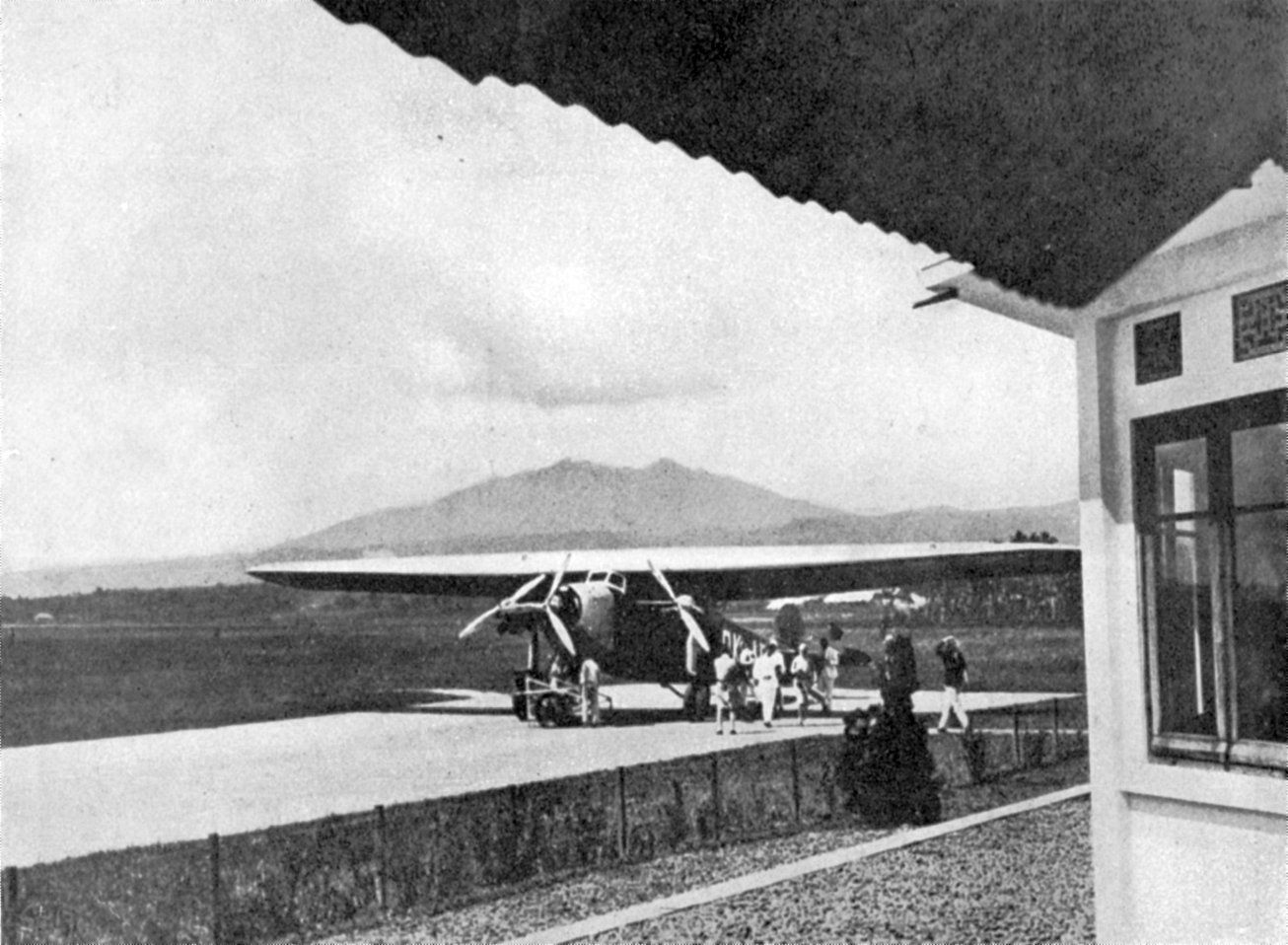

"The coquettish airport of Bandung".

Summer and winter route

KLM, which has become increasingly practical through experience, uses three itineraries on the Indies route, two of which differ significantly. In summer, its aircraft fly the Amsterdam-Athens route via Central Europe, with regular stops in Halle, Leipzig, and Budapest. In winter, however, the route across Central Europe, and especially the Balkans, is extremely difficult, causing significant delays due to fog, snowstorms, ice buildup on the wings, and other obstacles.

That is why during the winter months people go “around the South”, namely via Marseille, Rome and Brindisi.

If necessary, Paris can also be visited, and if Brindisi is unusable due to weather conditions, Bari can also be visited.

So there's a summer and a winter route. There's a variation on the summer route, namely that in June, July, and August, the Amsterdam-Baghdad distance is covered in three days instead of four, bringing the total travel time to nine. The longer daylight hours during the summer months allow for an early departure from Schiphol (4 a.m.) and a same-day arrival in Athens.