How to travel the Indies route

Passenger and freight transport is evolving. People often imagine that flying to the Dutch East Indies, with an average daily distance of 1,400 km, which equates to eight to nine hours in the air, is extremely tiring.

And yet this is a completely wrong representation.

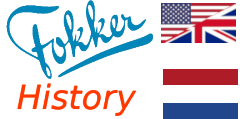

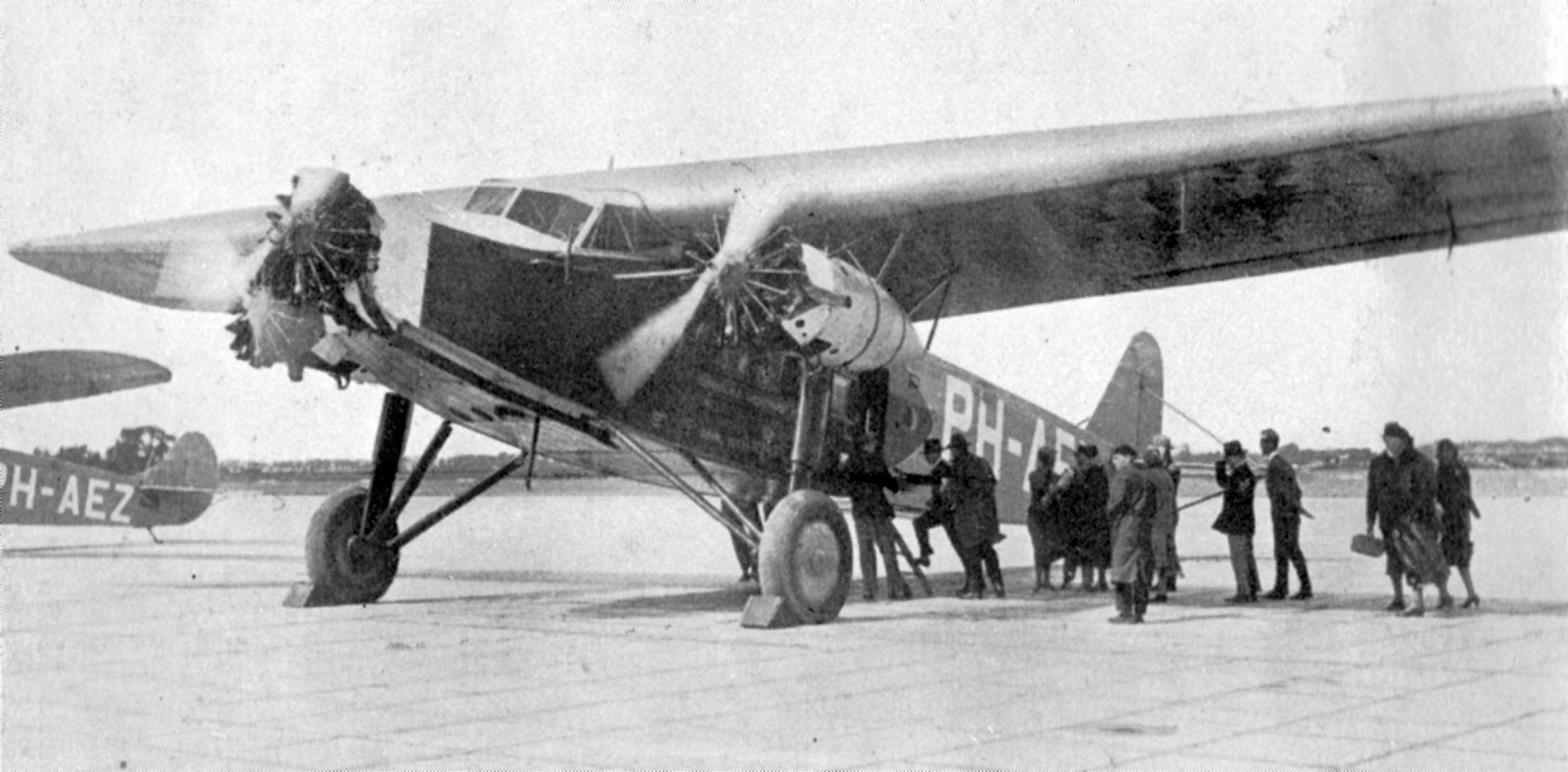

What does KLM's latest Indies airliner look like? A mighty aircraft with three massive 420-hp engines, a spacious cockpit, glass on all sides, and a wealth of instruments—but none of this matters to the passenger. For them, the cabin is important, and everyone who steps inside is amazed.

It is a large space where even the tallest man can move anywhere without bowing his head.

The cabin is also spacious on both sides and bright thanks to the many windows. Because the wing is high, the view is unobstructed and there is always shade in the cabin.

It is tastefully panelled in harmonious colours and fabrics.

There are large chairs made of nickel and red leather, the backs of which can be moved back. The seats can be extended, allowing you to sit upright as in an easy chair, or lie down for a nap.

In front of this chair is a folding table with a round holder to hold a drinking cup.

Each passenger receives two neatly sized suitcases from KLM. The larger one fits perfectly under the seat, while the smaller one is strapped to the back of the seat.

Against the back wall is a cabinet with washing facilities and next to it, hidden in a cupboard, the most delightful of the delights, the pantry.

Anyone who takes long trips knows how they'll spend their time watching, reading, sleeping, eating, and drinking. In that pantry are lunch boxes, which are replenished in every hotel each evening.

There's canned cheese and butter; there are cans that can be heated up, but sometimes also a few cold chickens. There are thermoses with hot and cold drinks, and paper cups.

The passenger has purchased his ticket and boards. His seat has been assigned. He departs at sunrise, often still in the darkness. The two pilots are at the controls, as long as the flight is in the dark. The radio operator sits on the left front, the key constantly moving up and down, then switches to "receive," and his hand begins to write. He is in contact with the ground stations, receives weather reports, receives bearings, is kept informed of approaching sandstorms, changes in the weather, and the condition of the airfields for the stopover. In short, all the valuable information necessary for safe navigation comes to him from the air.

In the seat behind him lies the engineer, sleeping. He's enjoying a well-deserved rest, having spent the previous evening preparing the plane, starting the engines this morning, taking notes, and now he's asleep. The heater is on when it's cold outside. As daylight comes, the first pilot comes inside and sits in the front-left seat. There are his chart table and the gauges, allowing him to plot his course.

Every now and then, a red light goes on for the radio operator, and we see him open the cockpit door and the pilot hands him a note containing an instruction. Immediately, we see the key working, the answer is written down, and given to the pilot.

After a few hours of flying, the engineer begins to stir. He's also the flight attendant. Then the mysterious cupboard opens, the bread board is pulled out, and everyone gets a second breakfast, including the pilot in the cockpit. One of the most pleasant moments of the trip.

Meanwhile, they are hurtling through the airspace at 180 km/h, deserts and jungles, mountain ranges and seas, cities and fishing fleets passing beneath the plane.

Around eleven in the morning the engines slow down, the airfield for the stopover is reached.

Soon the plane is right next to the fuel tank, the fuel pours into the tanks, and then the engines start humming again. It's time to board again, another few hours in the air until it reaches the final destination of that day's flight. The car immediately takes the passenger to their hotel, where the ration book works wonders. Because instead of bags of foreign currency, the KLM passenger has a ration book, which entitles them to accommodation and food anywhere along the route. They simply have to sign a ration book with their name, and the hotel provides them with what they need.

But it's still early in the day, and who wouldn't want to see Athens, Cairo, Baghdad, Jodhpur, and Calcutta? Travelers can do all of this. They have plenty of time; it's a wonderful change of pace from an already varied journey. Only, they have to go to bed early in the evening, because in the morning the alarm clock will ring, the car will be ready, and they'll be off to another country, perhaps even another continent.